6 Ways to Break Out of Depression

History suggests that sadness can have long-term upsides.

Post summary

We often think low moods and depression are entirely bad and stemming from defects in our brain.

But most cases of low mood and depression are better viewed as a helpful signal.

Today we’ll cover:

Why low mood and depression can be useful signals rather than problems.

A evolutionary theory about why we get depressed.

Why low mood and depression feel bad in the short-term but can help us in the long run.

The modern paradox of depression.

Six ways to leverage the power of low mood and depression to get unstuck and improve your mood and life.

Housekeeping

Full access to this post and its audio version is for Members of Two Percent.

Join us. Get valuable insights that provide the full story and actionable takeaways on our most pressing health and wellness issues today.

Shoutout to our partners:

Momentous made me feel good about supplements again. They also more than doubled the discount for Two Percent readers. Momentous is trusted by pro sports teams, the U.S. military—and Two Percent. My picks: Essential Plant Protein + Creatine. Use discount code EASTER for 35% off.

GOREWEAR designs endurance gear for Two Percenters. I live in their Concurve 2-in-1 Shorts during summer outdoor workouts. I also used their Drive Vest for windy hikes. Use code EASTER30 for 30% off your next order.

Audio version

It’s located at the bottom of this post.

The post

We tend to think mental health issues like depression are wholly bad, like something’s broken in our brains. And they are “bad” in the sense that they make us suffer.

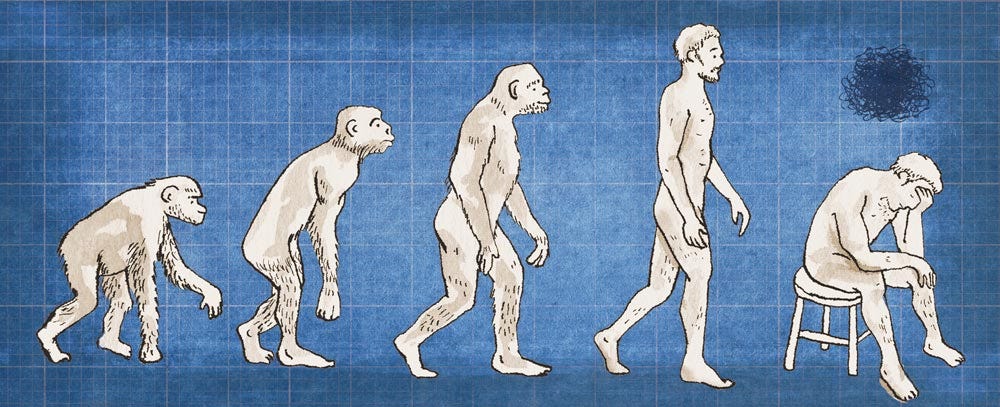

But low mood and depression often exist for a good reason. If they didn’t serve a purpose and didn’t help humans somehow, natural selection likely would have weeded them out. Yet it didn’t.

So the better question is: Why does depression exist—and when can it actually help us?

If we can answer that, we can see depression and everyday malaise differently, and maybe even more usefully.

Depression as a symptom, not a disorder

Traditional psychiatry often treats low mood and depression as disorders in and of themselves—regardless of what’s causing them1. They usually see them as coming from a disordered brain or chemical imbalance.

But the field of evolutionary psychology applies the principles of evolution and natural selection to understand human behavior and mental health. It sees many cases of depression as symptoms of a larger problem rather than problems themselves.

Think of this like a fever or pain. Both help protect us and tell us something’s wrong.

Without fever, our body couldn’t fight infections. We also wouldn’t know if we had an infection, and may leave it untreated and die.

Without pain, we’d ignore broken bones that needed downtime to heal or tumors that needed attention. (This is why the rare subset of people who don’t feel pain—a condition called CIP—tend to die young).

In medicine, treating symptoms alone is dumb. For example, if your stomach hurts, a good doctor won’t just give you pain pills. She’ll figure out why your stomach hurts. If you had appendicitis or an infection, the pain pills won’t solve the problem (and could do more harm than good).

Low mood and depression are characterized by low energy, pessimism, risk avoidance, withdrawal, and feeling demoralized.

So then the question becomes, what is depression and low mood a symptom of—and how do we fix it?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Two Percent with Michael Easter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.