No, Michael Phelps didn't eat 12,000 calories a day

We all suck at estimating how much we eat. Here's why that matters and how to know what you really eat so you can reach your goals.

Post summary

Michael Phelps told me that his daily 12,000-calorie diet was just a rumor.

But the rumor highlights an important fact: We all suck at estimating what and how much we eat.

We’ll dive into the wild psychology of why we’re wrong in what we eat, three reasons it’s so hard to know what you eat, and the solution to know what and how much you eat to hit your goals and find food freedom.

Housekeeping

This post and its audio version—like all Two Percent Wednesday and Friday posts—is for Members of Two Percent.

If you want all the good stuff Members get—the stuff that’ll help you live better—become a Member of Two Percent. Become a Member below.

If you’re thinking about joining us for the Don’t Die event, a quick heads up: It’s almost sold out. Join us. You’ll have fun and learn the fundamentals of self-reliance and health and fitness that actually transfers to health and longevity.

Audio/podcast version

P.S. You received the podcast version in your inbox today. Apologies! There’s a quirk in Substack where you have to unclick a button so the podcast doesn’t send to email. We’re seeing if Substack can turn that feature off so we don’t have to remember to unclick the button each time we post a podcast.

The post

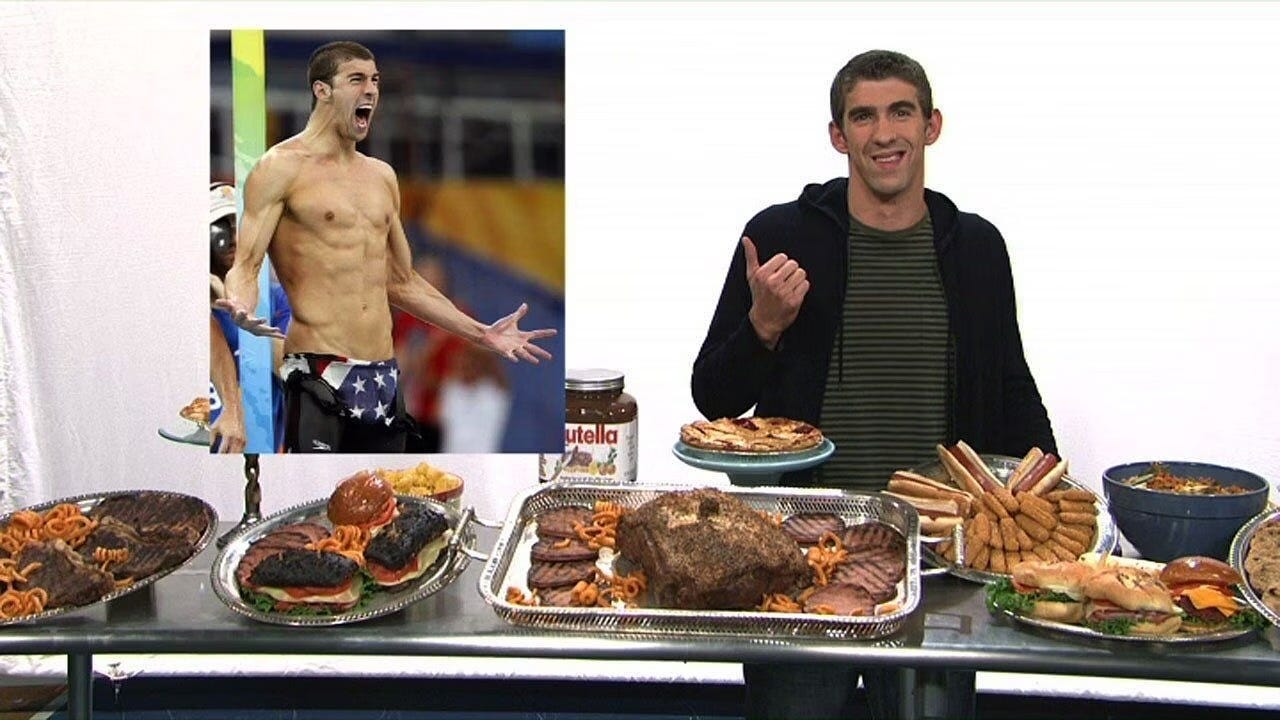

You probably remember the stories about Michael Phelps’ eating habits.

During the 2008 Olympics, Phelps got nearly as much attention for his daily 12,000-calorie diet than for the eight gold medals he won.

Outlets ranging from the Washington Post to the New York Times re-reported a tip that Phelps ate that amount of food. A YouTuber even challenged himself to eat Phelps’ 12,000-calorie diet. (YouTube remains unbeaten in dipshit content.)

But when I spoke to Phelps before the 2016 Olympic Games, he told me the diet was just a rumor.

Phelps laughed and said, “It definitely wasn’t that much,” and has since called those stories “ridiculous.”

The rumor happened like this: A reporter asked him about his diet and he vaguely rattled off what he thought he ate in a day. Sort of like, “Well, I think I ate a stack of pancakes and a bunch of eggs … maybe it was eight eggs? Then I had a sandwich and …”

The reporter then did some back-of-hand math and—bam—the 12,000 calorie myth was born.

He estimates he was eating around 8,000, which is about the average of other swimmers and endurance Olympians.

Obviously 8,000 calories a day is still a lot of food.

But it’s not 12,000. The 4,000-calorie difference would feed a non-Olympian for two days.

But Phelps isn’t unique in his hazy memories of the food he consumes. And this reporter wasn’t out of the ordinary for flubbing food calculations.

We all generally suck at two things:

Recalling what we ate.

Estimating how much we ate.

And this matters. Big time.

Understanding what and how much you eat is critical to controlling your weight and performing better. It allows you to eat in a way that helps you rather than hurts you.

Today we’ll cover:

The science of how incorrect we are when we estimate what and how much we eat.

Who is most likely to be most wrong in their eating estimates.

The three reasons we tend to get food estimates wrong.

Why knowing your intake matters.

A skill you can use to know what you really ate.

How to use the information to lose weight, gain it, maintain your current weight, or fuel a workout.

No, you didn’t actually eat that

Section summary: Research shows the average person eats anywhere from 300 to 700 more daily calories than they think.

We think we understand how and why we do the things we do. Especially our daily decisions like eating. But consider the following questions:

What did you eat yesterday?

How much, exactly?

Are you sure?

Research consistently shows you’re wrong.

For example, researchers associated with the Mayo Clinic recently testified that our recall of what we ate “bears little relation” to what we actually ate.

One study compared 24-hour food intake recalls, 4-day food records, and food frequency questionnaires to urine tests (a way of measuring energy and protein consumption).

The results: People ate far more than they’d reported.

This unawareness is a powerful factor in our weight.

The Mayo Clinic found that overweight people’s miscalculations are, on average, 300 percent greater than the thin peoples’.1

Another analysis discovered that people who are at a healthy weight underestimate their daily calorie intake by 281 calories, while obese people underestimate by 717, the equivalent of a Big Mac and small fries.

A now-famous 1992 study of overweight people who claimed to be unable to lose weight despite being utterly convinced that they were eating “just 1,200 calories a day” discovered via precise measurements that the people actually consumed about 2,000. Which is like saying, “Whoops, I ate half a pizza and forgot.”

Our unawareness wouldn’t matter if our food system was built on whole, single-ingredient foods. Those are harder to overeat to the point of serious weight gain.

But nearly 70 percent of our food is ultraprocessed. It’s stuff that’s crammed with calories and formulated to be consumed quickly. In this context, unawareness matters.

A team of NIH scientists discovered that 100 extra calories a day—either by burning less or eating more—over three years adds 10 pounds to the average person.

That same NIH team recently found that obesity began to skyrocket in 1978, when the average American added an average of 218 extra calories per day.

That figure alone, they believe, is enough to explain the rise in obesity. And obesity is a key risk factor for early death, killing 335,000 Americans a year.

The three reasons why and where we miscalculate

Section summary: We’re wired to overeat, modern foods pack a bigger punch, and we forget snacks and sauces.

There are three big reasons we underestimate what we eat.

1. Eating more has always made sense

For nearly all of history, food has been relatively scarce and survival relied on eating well when you had the opportunity. It’s almost like we’re “wired” to unconsciously eat more food rather than less.

It wasn’t until very recently in the grand scheme of time and space that “dieting,” trying to eat less, made sense for a large number of people.

What’s more, food scarcity shocks like World War I and the Great Depression taught entire generations to “clean their plate.”

President Herbert Hoover asked schoolchildren to pledge, “At table I’ll not leave a scrap of food upon my plate.” Harry Truman in 1947 created the “Clean Plate Club” to remind kids to eat all the food they could.

But when scarcity lifted, we didn’t resign our membership in the Clean Plate Club. Those generations taught their kids to clean their plates, who taught their kids to clean their plates, and so on.