Six Reasons to Appreciate Life Right Now

Post summary:

We’re covering:

What a desert bighorn taught me about life today.

The science of first-world problems.

Six graphs that might change your thinking.

Five actions to take to change your life right now.

Housekeeping:

Welcome to all of you who are new here! Here’s how the 2% Newsletter works:

Monday’s posts are always free. (Monday’s post covered how to talk to anyone. Read it here.)

Full access to Wednesday and Friday post are for Members of 2%, who are people who like to have fun and not die. (Non-Members get a preview with some useful stuff, but not the entire party.)

Sign up below to become a Member and get lots of good stuff.

I’m writing this from LAX. I was in town to record some podcasts. The conversations were a ton of fun. I’ll share them when they’re live.

The post

On Sunday, I ran in the desert mountains behind my home. It was one of fall’s first cool mornings, and the smell of sage lingered in the dry air.

After a few miles, the open desert funneled into a canyon. That’s when my dog, a German Shorthaired Pointer named Stockton, came to a quick halt.

He paused and sniffed the air, then pivoted off the trail.

Stockton is a hunting dog. When he quickly moves off the trail, he’s usually chasing a jackrabbit or chipmunk. But he just stood off the trail, enraptured.

And there it was: The corpse of a young desert bighorn sheep. (I decided not to include the photo, but you can see it here.)

Desert bighorns are some of the coolest, toughest animals in existence. They have all sorts of wild adaptations to survive the desert:

Their body temperature can safely fluctuate a few degrees to survive the extreme heat and cold of the desert.

They have cloven hoofs that allow them to be some of the best climbers in the desert (their defense mechanism is to go into jagged cliffs that other animals can’t).

They can go months without visiting a water source. They can lose up to 30 percent of their body weight in water and survive. Humans pass out when we lose 4% of our body weight in water and die at a 10% loss.

Still, 50 percent of desert bighorn sheep die in their first year or two of life. It’s hard to say how this one died. My guess is coyotes or a fall.

It reminded me that nature, although beautiful, is also brutal.

Teddy Roosevelt put it this way:

“Death by violence, death by cold, death by starvation—these are the normal endings of the stately and beautiful creatures of the wilderness. The sentimentalists who prattle about the peaceful life of nature do not realize its utter mercilessness; … life is hard and cruel for all the lower creatures, and for man also in what the sentimentalists call a ‘state of nature.’”

The merciless state of nature is the same state humans lived in for all but the most recent sliver of time.

Our ancestors frequently faced exposure to the elements, freak weather, encounters with wildlife, accidents brought on by unforgiving terrain, and much more. They faced constant and deep hunger. They worked hard to get their food and had to kill it themselves.

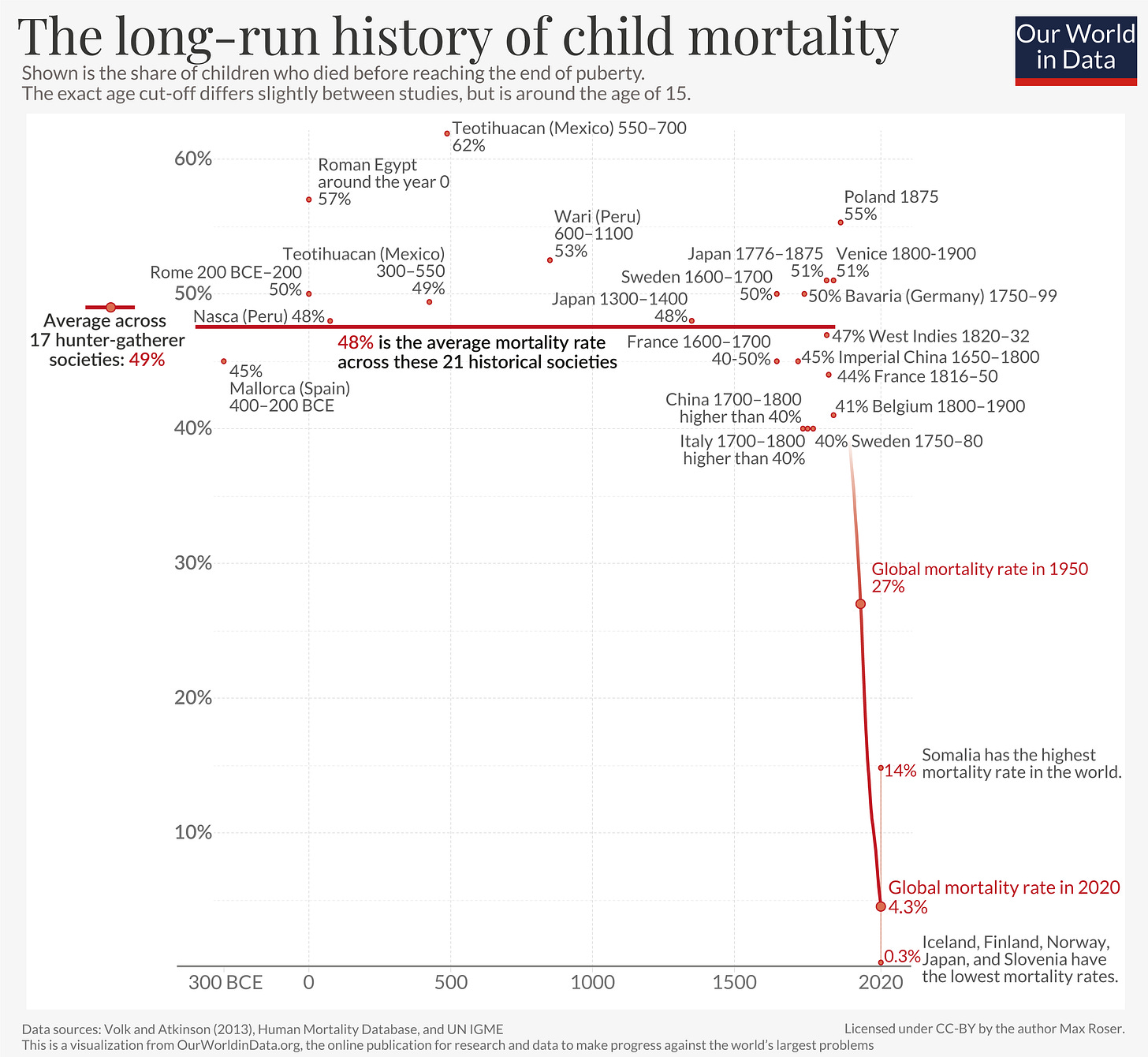

They died far younger on average than we do—roughly half of people died as infants or children.

Today, we spend 93 percent of our time indoors and live at 72 degrees. We rarely encounter wildlife that poses a danger to us. We navigate paved terrain in padded shoes and plush automobiles (FFS, my truck has a heated steering wheel).

We’re rarely hungry for any more than a few hours at a time, and hyper-caloric food is available with the touch of a few buttons. We offload the death of the animals we eat to secretive slaughterhouses.

This is a good thing overall*. It’s the result of progress. But as we’ve progressed, we haven’t necessarily stepped back and taken stock.

It’s easy to forget how good we have it in the grand scheme of time and space.

The science of first-world problems

Consider the phenomenon of “prevalence-induced concept change.” Think of it as “problem creep.”

Harvard psychologists discovered the theory in 2018, and I wrote about it in my book, The Comfort Crisis.

Through a series of experiments, the researchers discovered that as humans experience fewer problems, we don’t become more satisfied. We lower our threshold for what we consider a problem.

We end up with the same number of troubles. But thanks to progress, our problems have become progressively more hollow.

So the psychologists got to the heart of why many people can find an issue in nearly any situation, no matter how good we can have it relative to the grand sweep of humanity. We are always moving the goalpost. There is, quite literally, a scientific basis for first-world problems.

The world has indeed gotten better.

Six Points of Progress

You’re less likely to be living in extreme poverty

Until about 1850, about 80% of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty. Today, that figure is ~less than 10%. (Note: The figures are adjusted for inflation.)

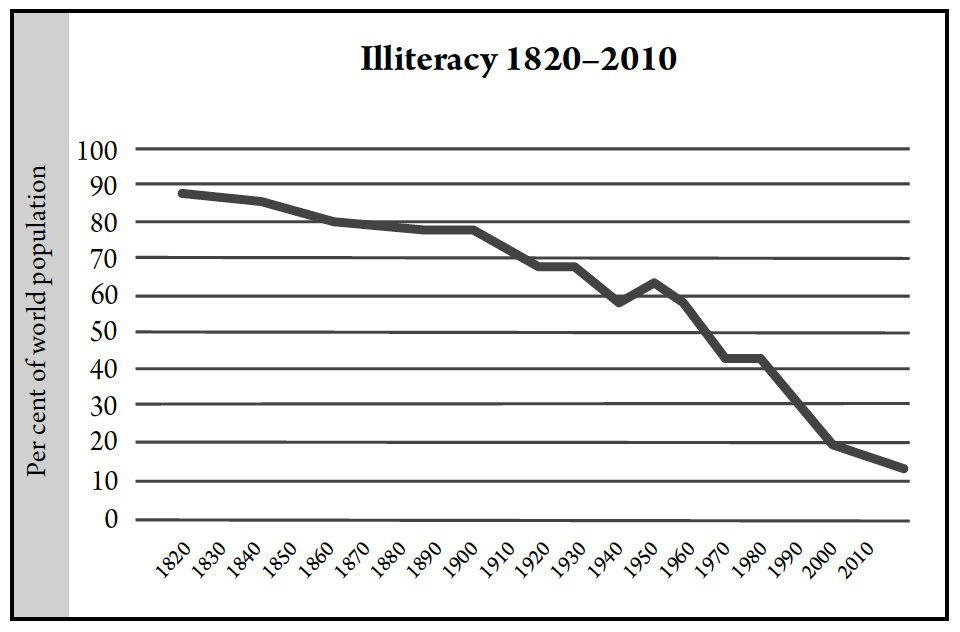

You’re more likely to be literate

Literacy is correlated with freedom and other critical aspects of human development. In the 1800s, 80 to 90 percent of the world was illiterate. Now the figure is about 10 percent and falling.

Your children are less likely to die

For most of time, 50 percent of the world died before hitting puberty. Today, developed countries have a youth mortality rate of 0.3 percent.

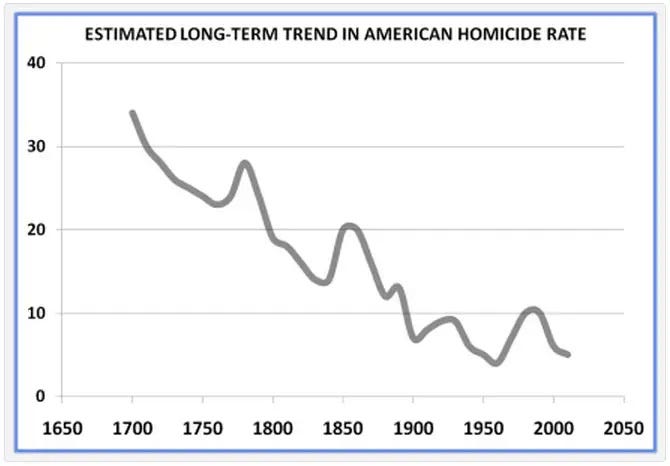

You’re less likely to get murdered

Here’s one reason people think the world is more violent.

You’re less likely to be hungry

This graph only goes back to 1970. The figures were far higher before The Green Revolution.

We care about the rights of more people and creatures

I could publish more of these graph. For example, domestic violence against women has dropped by more than 50 percent in just 20 years. Certain diseases have been eradicated (today, our biggest killers are a side effect of progress).

Things, of course, aren’t perfect. Not even close. We still have wars and many other issues. We must keep progressing.

But in the grand scheme of things, our situation is far, far better than it ever has been.

And yet …

… when you poll the average American, only 11 percent of people think the world is improving. We don’t consider the grand sweep of progress. Problem creep takes hold, and we think of a recent problem and let that blanket our worldview.

So how do you push back against problem creep?

Understanding the underlying mechanics of “problem creep” helps (that’s the point of this post!). But experience is the best teacher—it pushes the goalpost back the most.

There are many paths to the basket. But here are a few that have worked for me:

1. Spend time in nature

It’s where we glimpse what life was like for our ancestors. Like my experience with that desert bighorn.

As Dasho Karma Ura, a Bhutanese researcher, explained to me, “(Time in nature) can help you see yourself through a different perspective. Maybe you see a wild boar in the forest and wonder what his existence is like, and you realize his life is so much more of a struggle. Nature has both a beauty and a mortality to it.”

2. Travel

It exposes you to situations and perspectives different than your own. That can alter how you perceive your everyday life.

Fun(?) fact: People in my HOA bitch far more than the people I met while reporting in Iraq.

3. Volunteer

The Oklahoma State University happiness researcher, Alex Bishop, told me that volunteering seems to give people more perspective. And that increases life satisfaction.

This isn’t just a chicken-egg thing. Another study found:

(V)olunteering is associated not just with a higher wellbeing a priori, but with a positive change in wellbeing.

4. Think about death

From The Comfort Crisis:

A team of researchers at Eastern Washington University found that thinking about death enhances gratitude. The scientists wrote that when people think about death they “tend to recognize ‘what might not be’ and become more grateful for the life they now experience. Fully recognizing one’s own mortality may be an important aspect of the humble and grateful person. Perhaps when we recognize that death is a reality we all must face, we may then realize … that ‘Life is not only a pleasure but a kind of eccentric privilege.’”

5. Go without

This is a theme embedded in most major religions. Occasional deprivation makes the ordinary feel extraordinary. I explain this more in Scarcity Brain.

Have fun, don’t die, enjoy your time in nature.

-Michael

*Except for (probably) our modern slaughterhouse system. It’s good for feeding us meat, but doesn’t take into account suffering of sentient beings.

Nailed it!!! (As usual.)

I particularly like your asterisk. I came to hunting rather late in life, but it is one of the best things that ever happened to me. Being in nature. Taking an animal's life. Butchering that animal. All of that has put me much closer to Nature and given me an incredible appreciation for food, in general, and meat, in particular. People should not be so far removed from their food.

Keep up the great work, Michael.

I finished Scarcity Brain last week. I am reading "The Top Five Regrets of the Dying" by Bronnie Ware. I also visited the Abbaye Notre-Dame de Sénanque while in France last week. Points 4 and 5 are very much on my mind. As I move through my days, what used to trouble me now seems minor. The angst around "how will I get it all done" is more or less gone. When you go without and think about death being our only guarantee in life, unhelpful thought patterns, for me at least, are much easier to catch and reframe.