In our inaugural Q&A, we’re covering weighted sleds and the downsides of the optimization craze.

Why it matters: Question one investigates the upsides and downsides of a popular new(ish) fitness practice. Question two can help you find a more efficient (and saner) way to improve your health.

Quick housekeeping before the Q&A:

For some reason, the audio reading of the last post on sports nutrition didn’t make it in the email. The audio is now up on the post for those who prefer to listen. (Also, when I say, “for some reason,” I mean, “I probably clicked the wrong button.”)

Fun fact: You all apparently love … Uncrustables? It was one of the most clicked items in the last post.

Helpful info for everyone: A few of you told me that your employee wellness program covered your 2% Membership. Get the limited-time Launch Special below. Warning, side effects of becoming a Member include:

Heightened knowledge

Better health behaviors

Less stress around health behaviors

Better training and nutrition programs

Improved tolerance to dumb jokes like this one

… and much more.

Today is our inaugural Q&A. YES.

Last week we asked for submissions to the first 2% reader Q&A. We got a bunch and chose a couple.

Each month we’ll tackle two to three questions from you. You ask the question, then we’ll go down the research rabbit hole so you don’t have to. We’ll draw on past reporting, read new research, and speak to experts. Then we’ll tell you what we found.

Let’s roll …

Question 1: Is pulling or pushing a weighted sled good for you?

In short

It can be great. Maybe even uniquely great. But it comes with some caveats and a massive barrier to entry.

The details

This one's from Jordan Jonas. He’s the very tough human who won season six of the TV show Alone.

For those wondering what this question even means, a weighted sled is a piece of fitness equipment. You load it up with weight and then push, pull, or drag it.

Some weighted sleds have handles that you grab onto. Others have a rope that you attach to yourself.

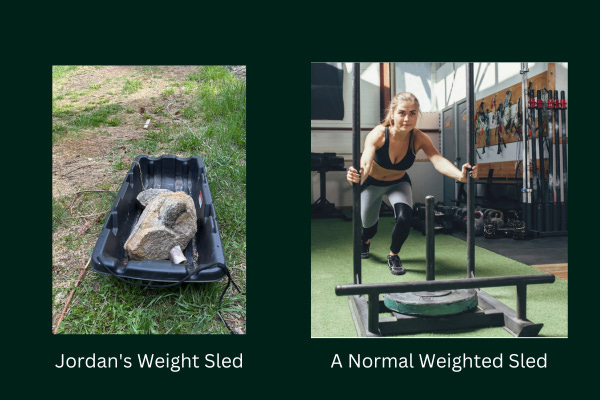

Jordan asked this question because he’d been pulling a weighted sled. The man lives in some off-the-grid location in Montana.

So I replied, “I’m picturing you pulling an actual sled filled with wood and rocks and maybe a downed moose.” His response: “Not far off.”

Humans have been dragging and pushing heavy stuff forever. We’d sometimes move the heavy animals we hunted that way.

But pushing and pulling weight as an exercise is relatively new. It’s been around for a handful of decades, but it was recently popularized by Ben Patrick, who spoke about the practice on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast. Sled dragging is now even in the Army Combat Fitness Test.

It’s a fantastic exercise. You can almost think of it like a relative of rucking. A few of its benefits:

It strengthens your legs and core. Your core must lock down as your legs become pistons propelling you against the weight.

It works your heart and lungs. Like rucking, you’re moving weight across a distance.

It can protect your knees. Backward sled drags hit a part of your knee called the vastus medialis oblique muscle (VMO). Strengthening this can help fix and prevent knee pain.

It can help you sprint faster. That’s according to a 2020 study that had high school athletes push a weighted sled.

It’s easy to recover from. Traditional lifting exercises, like a barbell squat, have a lowering and a lifting phase. That lowering phase is when your muscles become most damaged and, in turn, become sore afterward. Sled work doesn’t have that lowering phase.

How to start sledding

As weighted sled exercises rose in popularity, many people dove in too fast and got injured.

We called Kelly and Juliet Starrett, authors of Built To Move, a very useful book I recommend.

Kelly explained, “Pushing and dragging a sled for training is a great way to build fitness and a durable body. But a common problem for most people starting their sled journey is that they bring their well-developed fitness engine to this new skill and end up massively overdoing it. To prevent this, start dropping the sled into your warm-ups instead of building a whole training session around it.”

Easing in allows your body to adapt. A few pointers from Kelly:

“Keep the sled light so the sled feels more aerobic and less of a one rep max deadlift.”

“Build up volume over a couple of weeks. There is no world championship of sled dragging, so remember the magic of the sled comes with repeated exposure.”

Do it

Get a sled. Load it with weight. Push or drag the weight however you want. Follow Kelly’s advice for at least a month.

Slower and longer pushing and dragging makes it more of an aerobic exercise with an element of strength (much like rucking). I’ll do 30 minutes with a relatively lighter load once a week or so.

Heavier, shorter pushes and drags make it more of a strength exercise. Don’t be afraid to load the sled. Try five to ten rounds of 20 to 30 yards.

Sprinting with the sled will make it more of a power exercise. Warm up beforehand. Kelly said most problems come when people start sprinting with a sled while not being warmed up and not having done much sled work. Try five sprints of 15 to 30 yards.

Downsides of sled exercise

It’s totally impractical. For most people, anyway.

To push or pull a sled, you need a sled. That’ll cost you at least $150, probably more. Then you need weight plates—another hundred or more dollars.

More importantly, you need the space. Your backyard might work (but using it also might mess up your grass). If you drag the sled down the sidewalk or street, your neighbors will get annoyed because it can scar the pavement. And you’ll also look like a crazy person.

So you’ll probably have to travel somewhere else to use the sled. Like a park.

For example, I own a small sled from Rogue. I dig it. But to use it, I have to drive down the road to a park that has a half-mile stretch of wide dirt path. It’s a great area for doing the exercise.

But before the workout can begin, I have to load the equipment in my truck, then drive, then make two trips of about a quarter mile each to get the sled and weights to the dirt path. Hence, I pull the sled far less than I’d like.

The most accessible way to use a sled is probably to find a gym with sleds and a stretch of turf. Gyms like that are hard to find. But the good news is that more gyms are installing turf and sleds.

Two Simpler Solutions

Get a GORUCK Sandbag. Attach a rope to it. Drag it. Most active people should use between 60 and 100 pounds. Drag it for as long as you’d like. As always, the code EASTER gets you 10% off on all things GORUCK.

Do “Dead Sleds.” I got this from Jason Walsch. He trains a lot of actors who are preparing for film roles. When his clients can’t access a sled, he often has them do dead sleds. In short: Get on a treadmill. Don’t turn it on. Place your hands on the grips in front of you. Now push the belt backward with your legs. Continue marching this way. You can also do this while facing backward. (Note: Some people say this messes up treadmills. I have yet to see issues. But maybe try it on the gym’s treadmill.)

Question 2: How do I optimize X, Y, Z?

In short

You can’t optimize. You can solve problems.

The details

I received a few questions from readers who asked me how to optimize different facets of their life. Their exercise, their hormones, their eating, etc.

I’ve been noodling for awhile on why I don’t love the term “optimize.” Instead of answering any one of those questions questions, I’ll:

First, unpack the idea of optimization and why I think it can lead us astray.

Second, offer a question we can ask ourselves that might be more useful than trying to optimize.

The below is an attempt to sort out my thoughts. Please drop your thoughts into the comments—2% is a forum, not a soapbox.

On “Optimization”

To understand the possible downsides of looking at health through the lens of optimization, it helps to understand what the word means.

The word “optimize” first appeared in the 1800s. But it wasn’t until the 1940s that the word became common. The atomic age was ushering us into a technological future, and engineers and physicists began using it to mean “make as good as possible.”

For example, a 1960s-era Economist article said, “The shape of the aircraft—that is to say, its geometry—can be optimized for whatever it happens to be doing.” In the 70s, scientific papers were using the term in the context of chemical processes.

The word gained even more steam with the rise of personal computers and the internet in the 1990s and 2000s. We learned that tweaking some code could increase the likelihood that a user would do one thing and not another.

Programmers could optimize online algorithms and code to get you to spend more time on a social media platform. To increase the likelihood you’ll buy a product. To decrease the number of steps it takes for you to order delivery food.

“Optimize” became a buzzword in Silicon Valley.

From there, many wellness-conscious tech workers assumed that if you could optimize computer code, you could also optimize yourself. They applied the idea of “optimizing” to “ideas about the body, aspirations, habits, lifestyle, etc,” as researchers in Canada wrote.

People began trying to optimize their time, health, biology, thoughts, workouts, schedule, diet, and their (insert anything). Biohacking became a certifiable thing.

Over time, the idea of optimization left Silicon Valley and went mainstream. And you’ve surely experienced these ideas:

Put butter and MTC oils in your coffee to optimize your brain.

Meditate for X minutes to optimize your thoughts.

Work out this way and not that to optimize your hormones.

Sit in an ice bath for X minutes to optimize your mood.

Eat keto to optimize your fat burning.

On and on.

Of course, a lot of the advice wasn’t necessarily “bad.” It’s good to work out. It’s probably good to try to understand your thoughts. It’s good to try to eat healthy if you’re eating poorly.

But many of the practices around optimization are also somewhat strange, finicky, and based on very questionable science. They’re hyper-specific to a fault.

And there’s a big problem with the idea of optimization. Which brings us back to the question, “How do I optimize X, Y, Z.”

The problem with optimization

“Optimize” implies that there is an optimum, or some perfect destination. And while there might be optimal engineering for machines or strings of computer code, humans aren’t machines and rows of computer code.

Biology is extremely complex. We understand far less of it than you might think. And we’re all different.

It’s impossible to optimize complex, constantly changing biological systems that are all different. And even if we could reach some sort of optimal state in some facet of our life, we’d never know it.

Trying to optimize a system that can’t be optimized can lead us into misery. We’ll always be searching for some end destination that doesn’t exist rather than appreciating this moment and living well right here, right now. Even if the moment is imperfect.

That humans can’t be optimized is precisely why it’s incredible to be alive. If humans could be optimized, we’d be robots.

A better question to ask

I know my half-baked philosophical thought vomit isn’t actionable. And of course it’s important to continue to try to improve ourselves.

I’ll be thinking about this topic more. But in the meantime, here’s a more tactical way I’d approach the question.

Instead of asking, “How do I optimize X,” ask yourself, “What problem am I trying to solve?”

That question often leads to a more targeted and effective solution. You may even realize there’s no problem in the first place—that you’re striving for perfection in something that can never be perfect and that you’re fine as is.

For example, let’s say you first wanted to optimize your eating. What problem are you trying to solve by doing that? Do you feel like you’re overweight? Like you don’t have enough muscle? Like you feel low on energy?

Those three problems lead to entirely different solutions. The overweight person may benefit from understanding how much they eat and why and possibly reducing calories. The person who wanted more muscle might benefit from a change in workout programming. The person low on energy may want to look at their sleep habits.

You get the point.

Thanks for reading. Have fun, don’t die, push heavy stuff, and solve problems.

-Michael

Love this Q and A format. A note on the sled push/drag: I live in Austin, TX and there is a gym here called Atomic Athlete (https://atomic-athlete.com/) that certainly incorporates sled pushes and drags in their programming, but they also lean HEAVILY on tire drags. By getting an old tire, loading it up with a sandbag or weight plates, you can have the effectiveness of the sled drag without spending much money.

I always appreciate your takes on these things Michael! I feel like the optimization craze led me to develop some fairly unhealthy habits and some anxiety when things weren't perfectly "optimized" (whatever that means). Having a more intuitive and flexible approach while still greatly respecting the research has not only made me feel much healthier, but also has made life a lot more enjoyable.