How to Use Boredom as a Performance Enhancer

Our inability to do nothing is killing our best ideas. Here's the uncomfortable, 20-minute fix to reclaim your edge.

I spent 14 hours on a plane yesterday. That’s a long time strapped into a seat.

To make use of it, I read and edited a first draft of my forthcoming book.

But I have a problem.

There’s one chapter that’s been driving me crazy. Ask Leah. When we walk our dogs, I talk about it incessantly. I’ve written and rewritten around 50 drafts of this chapter, and still can’t figure out the right way in or how to develop the argument once I get there.

As I read the manuscript on the plane, it became clear that sitting in a metal tube at 35,000 feet wasn’t going to produce a grand revelation. So I skipped the chapter.

Ten hours later, I’d finished reading and notating the rest of the book. My brain was fried. I needed a break.

I looked up at the screen embedded in the seat in front of me. It offered thousands of movies, TV shows, and podcasts. When we need a break, most of us flip on a screen.

But it turns out there are two very different ways to rest the mind:

One is to consume mindless, screen-based media. It’s easy, low-effort, and immediately satisfying. But it rarely delivers lasting benefits.

The other is to do nothing—to sit with boredom and see where it leads. It’s uncomfortable at first, but it often takes us somewhere useful.

I stumbled into the second.

I put on my noise-cancelling headphones—no music—and just sat there, looking into the black screen like a psychopath.

Boredom gripped me quickly. The discomfort of just sitting there doing nothing was a fresh hell.

This isn’t just me. In a famous set of studies1, many people disliked being alone with their thoughts so much that they’d rather shock themselves than sit there doing nothing.

At first, my thoughts wandered into nonsense: How far is the rental car place from the airport? Is this jet lag going to mildly wreck me or totally wreck me? What are my dogs doing right now?

But I stayed with it.

And after about 15 minutes, my mind drifted back to that miserable chapter. What was working with it (not much!). What sucked (a lot!). Then—unexpectedly—I started thinking up entirely new ways to open it. New scenes. Better structure. A way to pull material from another chapter to make the argument land.

I think I found the answer.

It only took 50 drafts, hours of blabbering at Leah, and about 15 minutes of being bored out of my mind somewhere over the Atlantic.

I told you that to tell you this: Boredom sucks, but it’s a hell of a drug for creativity.

Today you’ll learn:

Why your ability to “sit with boredom” is a 3x better predictor of career success than your intelligence.

The specific timeline your brain needs to move from “psychological discomfort” to “breakthrough mode.”

Why your current attempts at reducing screen time are likely failing your creativity.

A 20-minute weekly practice for scheduling boredom to solve your hardest problems.

In case you missed it:

On Wednesday, we gave you an excellence audit. It’ll help you ruthlessly eliminate what’s holding you back and help you find and complete a worthwhile goal.

On Friday, we ran My Favorite Exercise: Volume 5. It’s my favorite squat exercise. It’s safe, makes you better at life, and works your core harder than planks.

Check out Montana Knife Company—a gear company that helps you not die

I’ve been carrying MKC knives into the wilderness for years. They’re bombproof, razor sharp out of the box, and made in Montana. My everyday carry: The Mini Speedgoat 2.0. Check them out here and mention you heard about MKC from Two Percent. MKC knives sell out quickly, but here’s what’s currently in stock.

The Creativity Advantage

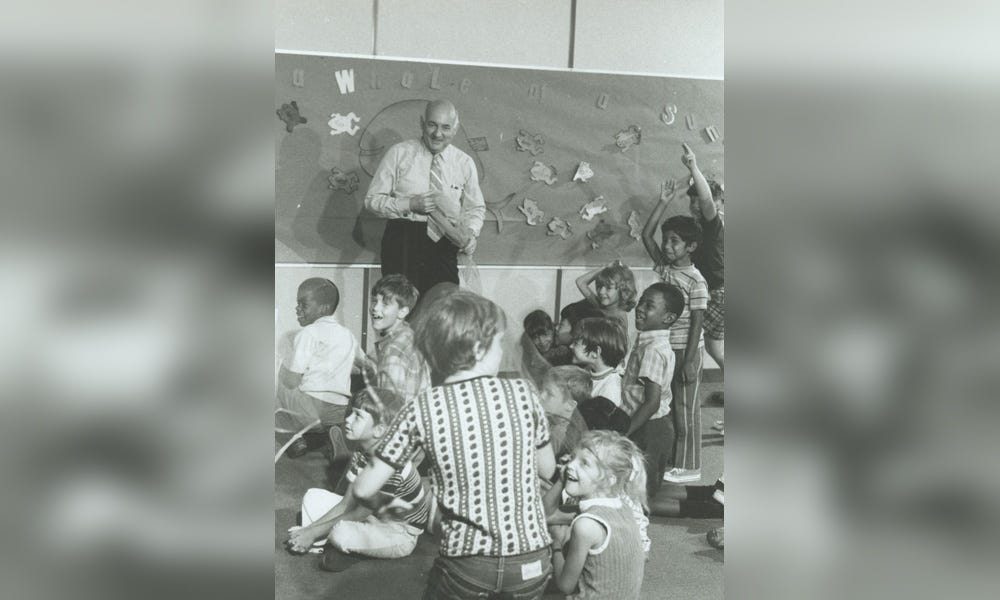

In the 1950s, the psychologist Ellis Paul Torrance noticed something off-target about American classrooms.

Teachers favored the subdued, book-smart kids. They didn’t much like the kids who had tons of energy and too many ideas—the kids who’d think up odd interpretations of readings, inventive excuses for why they didn’t do their homework, and morph into mad scientists every lab day.

The system deemed these kids “bad.” But Torrance thought they were misunderstood.

Because if a problem comes up in the real world, all the book-smart kids look for an answer in … a book. But what if the answer isn’t there? Then a person needs to get creative.

That insight led Torrance to devote his life to studying creative thinking. In 1958, he developed the “Torrance Test.” It’s since become the gold standard for gauging creativity.

He had a large group of children in the Minnesota public school system take the test. It includes exercises like showing a kid a toy and asking her, “How would you improve this toy to make it more fun?”

The results were striking.

The kids who came up with more and better ideas in the initial tests were the ones who became the most accomplished adults. They were successful inventors and architects, CEOs and college presidents, authors and diplomats, etc.

Torrance testing, in fact, often beats IQ testing—a recent study of Torrance’s kids found that creativity was a threefold better predictor of much of the students’ accomplishment compared to their IQ scores.

The Creativity Crisis

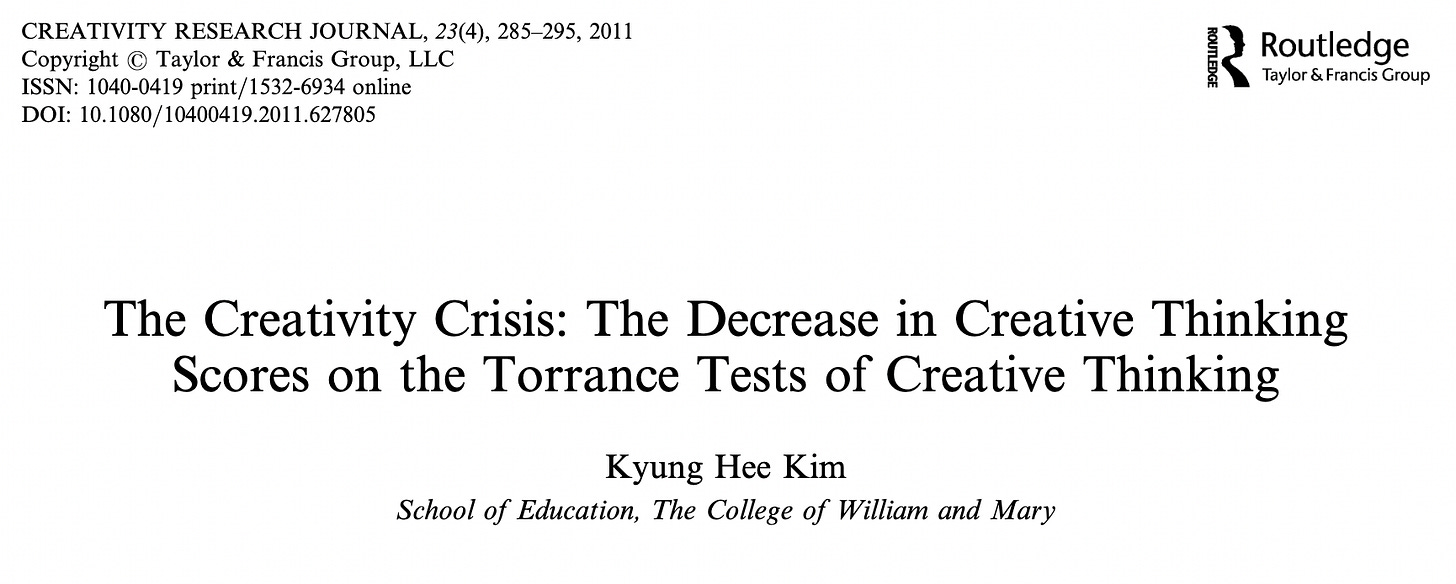

Torrance showed us how valuable creativity is. But newer research suggests it’s disappearing.

A researcher at the University of William and Mary recently analyzed 300,000 Torrance Test scores dating back to the 1950s. She found2 that creativity scores began to nosedive around 1990 and have continued to fall since.

She concluded that we’re now facing a “creativity crisis.”

This is bad news—especially in a world where most of us no longer work with our hands, but with our minds.

She blamed our hurried, over-scheduled lives and “ever-increasing amounts of (time) interacting with electronic entertainment devices.”

The average American now spends more than 12 hours engaged with digital media (up 1 hour since I wrote The Comfort Crisis).

The Boredom Solution

What happened to me on that plane is exactly how boredom is supposed to work.

To understand why boredom is useful today, you have to understand what it is.

Boredom is a psychological discomfort. It’s a signal that what you’re doing is no longer delivering a meaningful return. The process works like this:

You’re engaged in an activity, but it stops providing useful feedback (e.g. progress, stimulation, benefits).

The discomfort of boredom kicks in.

Your mind begins to wander

That wandering produces new, often useful ideas.

Boredom isn’t a flaw. It’s an ancient survival tool. As humans evolved, boredom helped us avoid wasting time on low-return activities. If hunting wasn’t working, boredom nudged us to consider other options—gathering plants, moving locations, trying a new strategy.

When boredom appears, our attention turns inward, and our mind wanders. And that inward focus—mind wandering—is a powerful driver of creativity. Ideation and creativity happen when we’re inside our own heads, dreaming up big ideas rather than watching or listening to someone else’s ideas through a screen or speakers.

It’s also a mental rest state that restores and rebuilds the resources needed to work better and more efficiently. Mind wandering is critical to get shit done, tap into creativity, and process complicated information.

This is why studies have found that bored people score significantly higher on creativity tests. It’s also why people often report having their best ideas in the shower—it’s a time of pure mind wandering.

It’s also important to note that, as the psychologist and neuroscientist James Danckert told me, “boredom is neither good nor bad.” It really depends on where it takes you. My point: We have so many easy and effortless escapes from boredom today (screens), that we never find out where it can take us.

Which brings us to our next topic …

The Problem with “Less Phone”

We all know we spend too much time on our phones.

There are thousands of articles offering tips on how to use your phone less. But these often miss an important point.

When people reduce their phone screen time, they often get bored—and immediately replace it with another screen, short-circuiting the very mental state that drives creativity.

Taking a couple of hours off your phone screen time only to add in more TV time is like replacing cigarettes with chewing tobacco.

The takeaway is clear: Creativity requires moments of boredom—moments when the mind is allowed to wander without external input.

Steve Jobs once said, “I’m a big believer in boredom. All the [technology] stuff is wonderful, but having nothing to do can be wonderful, too.”

Try a 20-Minute Boredom Block

Despite what productivity culture tells us, doing nothing is sometimes the most productive move you can make.

Boredom is uncomfortable—but that discomfort is what opens the door to original thought. Before constant stimulation, boredom was a regular feature of human life, delivering benefits essential to creativity, sanity, and meaning.

That moment on the plane when my hand moved toward the screen? I’m glad I pulled it back. The hour I spent with my thoughts was worth more than anything a movie could have offered.

How to do it

Once this week, block off 20 minutes and do absolutely nothing.

No phone. No music. No podcast. No book.

Sit. Walk. Stare. Let your mind itch and wander.

The first 5-10 minutes will feel pointless and uncomfortable. That’s the cost of entry. If you stay with it, your mind will usually flip into a different mode—one that connects dots, revisits hard problems, and surfaces ideas you couldn’t force on demand.

If sitting feels hellish, go for a phone-free walk. A Stanford study3 found that walking reliably increases creative output compared to sitting.

Have fun, don’t die, reclaim boredom.

Michael

Audio version

Timothy D. Wilson et al., Just think: The challenges of the disengaged mind. Science; 345,75-77(2014).

Kim, K. H. (2011). The Creativity Crisis: The Decrease in Creative Thinking Scores on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 23(4), 285–295.

Oppezzo, M., & Schwartz, D. L. (2014). Give your ideas some legs: The positive effect of walking on creative thinking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40(4), 1142–1152.

Just goes to show the wisdom of A.A. Milne when Pooh says "Sometimes I sits and thinks, and sometimes I just sits."

I started noticing a lot of blockers getting resolved for me in the sauna. I genuinely wondered if it was the heat or discomfort but I think that sitting and staring at the control knob of the heater for 20 minutes allowed my mind to wander into solutions.

This is a cornerstone piece for creators and problem solvers!