A twisted 1920s experiment that explains your fears

Fear is a story. Change the story, change your life.

In this post you’ll learn:

-A twisted scientific experiment that shows the true nature of fear.

-What neuroscience gets wrong about fear and anxiety.

-What fear really is.

-Why fear is often based on a story, not reality.

-How to overcome fear using proven science (without medication).

Housekeeping

This post, like all Monday Two Percent posts, is free for all subscribers. But only Members get full access to all three of our weekly posts and their audio versions.

Become a Member here:

ICYMI:

On Wednesday, we covered a nutrition rule that cuts through nonsense. It’s helped me navigate the chaotic world of nutrition information, and improved my eating (and sanity).

On Friday, we ran a Q&A where I covered topics like my new rucking book, and the latest on boredom, recovery, and what actually makes us healthier.

Audio version

The post

Halloween is coming, so today we’re covering fear.

Fear is one of the most primal and uncomfortable feelings a human can have. And despite the world being safer than ever, fear has been trending upward.

60 percent of Americans report at least some fear, while 41 percent of people experience high levels of it.

Despite violent crime falling by 50 percent1 from 1993 to 2022, half of us fear for our personal safety, a three-decade high.

The intensity of our fears is also climbing. Four out of ten people feel more anxious today than they did last year—which was a rise from the year before, and a rise from the year before that, and so on and so forth.

This phenomenon of fearing so much is especially prominent among the middle and upper-middle classes, with researchers calling this group “the anxious middle.” That looming, inexplicable fear is one reason why only 16 percent of the middle class is highly satisfied with their lives2.

A twisted fear experiment

Psychologists began to understand what causes fear through a controversial experiment—the kind that would never get past ethics boards today.

In the 1920s, a psychologist named John Watson conducted the “Little Albert experiment.” Watson got a nine-month old kid named Albert B. He chose Albert because Albert was a happy kid who didn’t display much fear.

At the start of the experiment, Watson had Albert play with various animals and objects. For example, a white rat, a rabbit, a dog, a monkey, wool, a mask. Albert was totally fine with them all.

Then Watson figured out what startled Albert. The answer was striking a bar with a hammer behind Albert, creating a surprise, jarring noise. That loud, unpredictable noise disturbed and upset Albert.

Knowing what upset Albert, Watson then started striking the bar with the hammer behind Albert’s back any time he’d bring out the white rat. I.e., White rat appears, bar gets struck, Albert gets startled and cries.

Soon enough, Albert would get afraid and cry anytime he saw the white rat, even if Watson didn’t strike the bar. Albert equated white rats with loud, jarring noises, so he began fearing the animals.

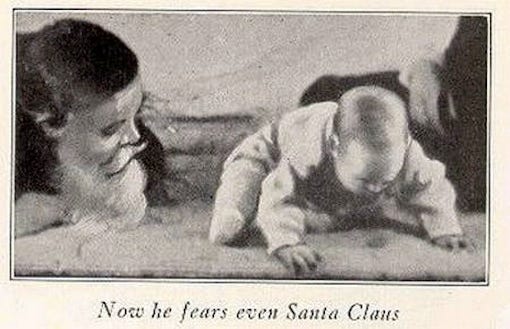

But here’s the wild thing: Albert didn’t just become afraid of white rats. His fear began to generalize to other white, furry things. For example, he started to get scared around white fur coats, white dogs, and even a Santa Claus mask with a big white beard.

The real science of fear

I recently spoke to Joseph LeDoux. He’s a Neuroscientist at New York University and arguably the world’s foremost expert on fear.

The experiments from the 1920s suggested that fear was something we learned.

But with the rise of neuroscience in the 1980s, scientists got excited about the inner workings of the brain. They came to believe that fear was a hardwired state residing entirely in our neuroanatomy.

They thought it rose from the amygdala, a small, almond-shaped structure in our brains. Still today, if you look up what the amygdala does, you’ll get information that it produces fear (among other things).

But through research, LeDoux realized the amygdala doesn’t produce fear. “I blew the whistle,” he said. “I said, ‘We’re not studying fear.’ In these rat experiments, we’re studying defensive behaviors that allow us to respond a certain way to stimuli.”

His work shows that the amygdala is like a smoke detector: fast, automatic, and unconscious. It spots dangers and triggers reflexes (startle, freeze, spike in heart rate).

Fear, on the other hand, is the conscious story you build immediately after the alarm goes off. It’s how we interpret what’s happening based on our past, culture, and context.

“Each emotion we have is culturally situated, and our culture provides a kind of template, or schema, upon which we interpret situations,” LeDoux told me. “So as soon as you go into a situation, the schema provides you with all of the information to interpret that situation. And from there, you construct these stories that explain the situation to you internally, which is the basis of your conscious experience. So for me, fear is not something that pops up out of the amygdala. Fear is the interpretation of events.”

In Little Albert’s case, he told himself a story that white furry things equal startling, terrible sounds—so he began to fear them.

Here are a few cultural examples of how stories shape fear:

Spiders: Western cultures often have a strong fear of spiders and high rates of arachnophobia. But in parts of West Africa and South America, spiders are frequently used as food and seen as good.

Owls: In much of North America, owls symbolize wisdom, and we get excited and happy when we see them. In parts of East Africa and India, owls are feared as bringers of death or bad luck.

Public speaking: In the U.S., where we value individuality, public speaking ranks as a top fear. In collectivist cultures more focused on the group instead of the individual, fear centers less on standing out and more on not disturbing group harmony—so public speaking fears are not as common or acute.

Where medications fail

LeDoux pointed out that fear being a story is why using medications to deal with fear and anxiety often fails.

“Drugs don’t really work to make people feel better,” he said. Instead, they simply turn down your threat detection system and arousal.

“But you’re still in that mental fear state. So how do you change that fear state? Ultimately, to change a mental state, you have to interact at a mental state level. You can’t just swallow a pill. There’s no magic [biological] target that’s going to [change your story and] make you feel better.”

LeDoux compared the relationship between fear and anti-anxiety medications to being in a restaurant playing loud, awful music. The obnoxious music is like fear.

Taking a medication helps you tolerate the obnoxious music, but it doesn’t actually get rid of it. It’s still there, being obnoxious, but you’re just less reactive to it.

To get rid of the music, you have to change your story.

To beat fear, confront your story

The Little Albert experiment and LeDoux’s work hold lessons for us.

We all have our own version of a white rat: Something we fear that is probably benign and that, at some point in our life, we learned to fear. That could be because of our parents, media, an experience that paired with aversive stimuli, etc.

But most fears stem from the story we tell ourselves. And if fear is often a story, how do you tell yourself a different story?

You have to do the uncomfortable thing: put yourself in a position to feel that fear and realize it’s probably unfounded.

Scientists call this “exposure therapy.”

In it, you confront your fears and anxieties in a safe environment. You start with less intense situations where you face your fear and work up to more intense situations.

To bring it back to Little Albert, it would work like this:

Step one: Put Albert in a room and very slowly bring in a white rat in a cage and set it across the room. Yes, he’d have some fear. But the rat is caged and far away, so he could sit with it.

Step two: Let the rat out of the cage and confine it to the other side of the room. Albert would still have some fear, but a little less than he would have had we not started with the rat in the cage. Eventually, he’d get comfortable with the rat at the other end of the room.

Step three: Then we’d perhaps let the rat run about its business in the room. This would be fear-provoking for Albert, but he’d eventually calm down.

Step four: Next, we might have a handler hold the white rat and bring it closer to little Albert, who would feel fear but eventually chill out.

And so on and so forth—slow, controlled exposure, fear fading to calm—until little Albert was at step five: playing with the white rat and considering it a close friend. And also playing with white dogs, hugging his mom while she was wearing a white fur coat, and smiling while sitting on Santa’s lap in Christmas photos.

Research shows exposure therapy works. One meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials—where scientists take the best studies and cumulatively look for what they found—discovered that exposure therapy significantly lessened PTSD symptoms. Seventy percent of people with PTSD who went through exposure therapy no longer showed symptoms3.

Another study found that up to 75% of people who went through exposure therapy for social anxiety saw massive reductions in fear of social situations4.

This type of slow confrontation with the uncomfortable is truly wonderful for phobias. Just a single session of exposure therapy seems to work. Studies show 90 percent of people with specific phobias get far better after going through exposure therapy5.

And these changes aren’t a temporary stay. The research shows that the vast majority of people with PTSD and OCD who went through exposure therapy were still benefiting from it five years later.

How to use it

Exposure is uncomfortable. But that’s why it works.

And if your fear is truly debilitating, you should go through exposure with a trained practitioner.

But for everyday stuff, you can overcome fear yourself. Here’s how:

1. Identify your fear

What is it you’re afraid of? Bugs? Social situations? Speaking in public?

Get specific about the situation and what you fear about it. The more specific you get, the better you can target the fear. For example, “speaking to someone I don’t know in an uncontrolled setting” is more actionable than “social anxiety.”

2. Create a fear hierarchy

Write down situations where that fear might pop up, ranking them from the situations that sound sort of scary to totally scary. For example, if your fear was having to speak to someone you don’t know in an uncontrolled setting, your ranking list might look like this:

(easiest) Saying hello to a neighbor.

Starting a conversation with the person next to you in a checkout line.

Talking to someone you don’t know at a social event.

(hardest) Giving a presentation at work.

3. Start tackling that hierarchy

Start with the first item. Yes, it’ll be uncomfortable at first. But say hi to that neighbor. Then do it again and again until it feels routine. Then move up the hierarchy. Say hi to the random person in line. Ask “How are you?” Chat. Repeat the process.

4. Question your story

As you tackle the hierarchy, begin asking yourself what story you’re telling yourself around your fear.

Why do you have that social anxiety? What do you believe is going to happen in social situations? Is the story you’re telling yourself grounded in reality? Where might your story be wrong? Unpeel the story to the best of your ability and let that guide you.

The goal is to explore and move up the hierarchy gradually. Lean into that uncomfortable space slowly but surely.

Soon enough, you might find that your story is bullshit—and you’ll find freedom.

Have fun, don’t die, do something scary,

Michael

Thanks to Function Health

Function Health offers 5x deeper insights into your health than typical bloodwork. They’re also offering a $100 discount right now! You’ll learn critical information that can guide you into feeling better every day. Head to my landing page at functionhealth.com/michaeleaster to sign up with your credit applied.

Gramlich, J. (2024, April 24). What the data says about crime in the U.S. Pew Research Center.

Pew Research Center. (2008, July 29). III. The anxious middle.

McSweeney, L. B., Rauch, S. A. M., Norman, S. B., & Hamblen, J. L. (n.d.). Prolonged exposure for PTSD. National Center for PTSD, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Morina, N., Seidemann, J., & Buhlmann, U. (2023). The effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy for social anxiety disorder in routine clinical practice. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 30(2), 335-343.

Ost LG. One-session treatment for specific phobias. Behav Res Ther. 1989;27(1):1-7. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90113-7. PMID: 2914000.

Poor little Albert!

We are born with two innate fears for survival: loud noises and falling.

We learn the rest via exposure, conditioning and/or today, 'bubble-wrapping from an ever present onslaught of a fear-mongering social media.' Very sad!

We lack spontaneity and hands-on learn by doing and failing.

Irrational fears are the norm, and unfortunately are 'treated' with MEDS, without ever getting to the root cause. This is woven into how we perceive people, places and things as chronic DIStressors.

NO, I am NOT talking about abuse, violent environments, serious accidents, injuries, PTSD, etc. or grief from the loss of a loved one.

It cracks me up ... feeling 'stressed' [whatever that means] .... of course breathwork, meditation, movement, etc. play a key role in restoring homeostasis, from SNS back to PNS dominance. Good!

But do we ever directly confront and tackle the stressor strategically? Do we actively work towards changing our perception of the so-called DIStressor?

We all have fears, and experience Distress. But are they affecting how we function in our daily lives, work, social connections? Are they promulgating irrational fears in our kids? our elders?

Stress is the means to learning, growth and discovery. Overcoming fears does the same, providing a window of opportunity for nurturing our Purpose [reasons to get up the morning bigger than self].

👍⛰️