I didn't think I needed morning sunlight. Here's why I was wrong.

Is getting sunlight in the morning actually important for health?

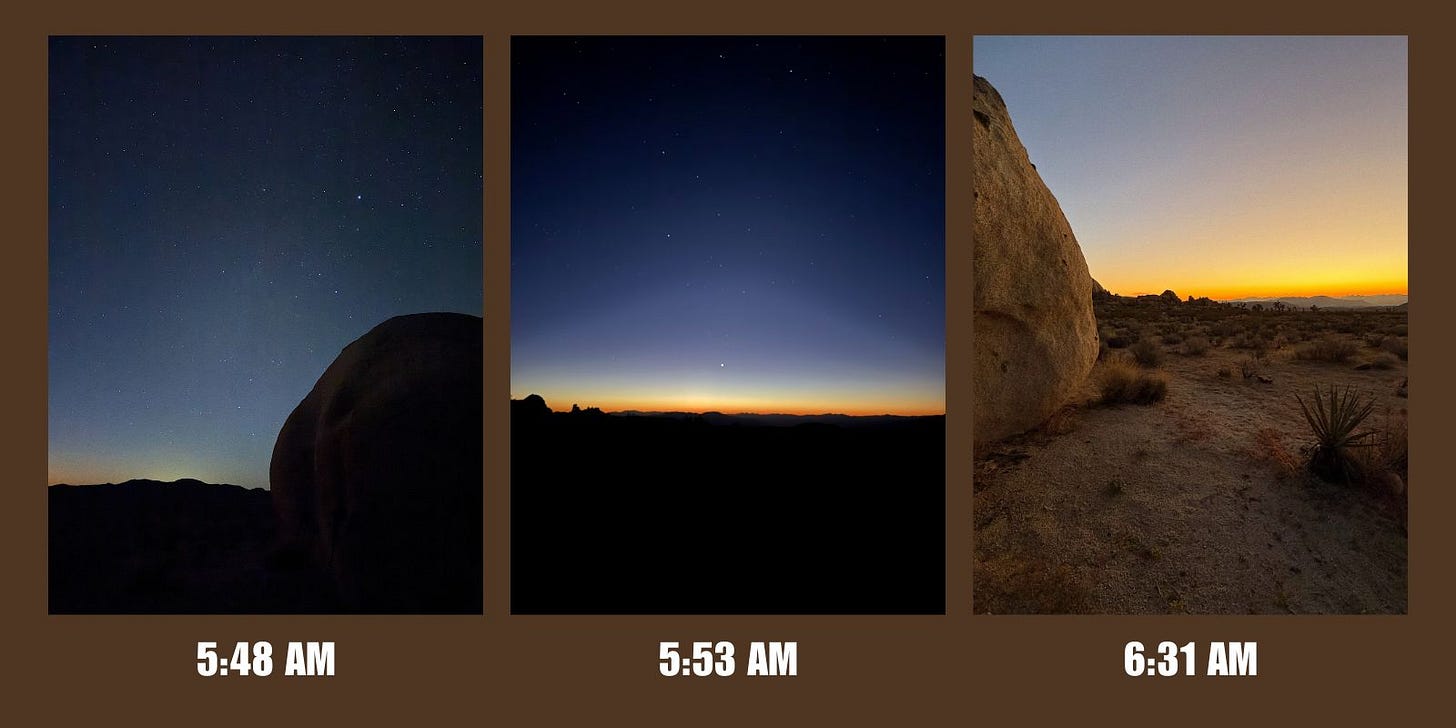

4:50 a.m., Joshua Tree National Park. My friend Matt Sherman eased a rental car into a dirt pullout.

The desert was black. We stepped out of the warm car into a 40-degree morning, layered up, turned on headlamps, and started hiking.

Matt and I hiked the Hayduke Trail together, but he’s logged far more miles—something like 30,000 around the world.

A year earlier, he’d discovered “One of my favorite campsites of all time, and probably the best spot in the world to watch the sunrise.” That’s where we were headed.

Our headlamps caught the haunting frames of Joshua Trees as we hiked under the stars. “Here,” Matt said after 40 minutes, and peeled off the trail.

We sat and waited for the show.

If you’ve listened to a health podcast in the last half-decade, you’ve probably heard that you should get sunlight early in the morning. It’s supposedly magical for sleep, metabolism, mood, focus, etc, etc, etc.

As we sat, I wondered about those claims. So I decided to investigate.

Today you’ll learn:

Whether getting morning sun is real science or pseudoscience.

How 2.5 million years of evolution wired your eyes to act as a “start button” and “off button.”

How I think about getting morning sunlight (and a simple 5-minute action that might fix your sleep and improve your life).

In case you missed it

On Wednesday, we explained why your “energy” has nothing to do with your performance. This post gave readers many “aha” moments.

On Friday, we ran the Gear Not Stuff Holiday Gift Guide, and Two Percenters loved it: 7 categories, 28 items of the year’s best gear not stuff.

P.S. December’s Burn the Ships workout drops this Friday (we swapped them so you’d have more time for gift buying).

Two Percent has the best d*mn partners on Earth

🚨 New partner alert: Montana Knife Company. I’ve been carrying MKC knives into the wilderness for a few years. They’re bombproof, razor sharp out of the box, and made in Montana. My everyday carry: The Mini Speedgoat 2.0. Check them out here and mention you heard about MKC from Two Percent.

Jaspr air purifiers. Air quality is a massively overlooked health metric. I consider Jaspr my #1 home health tool. Most health-promoting things require effort—but Jaspr is an exception. Just plug it in and remember to breathe. Get a discount through this link.

The desert is getting cold, and GOREWEAR is saving my life on trail runs. I love the CONCURVE WINDSTOPPER insulated jacket, which cuts the wind and cold. EASTER gets you 30% off your first GOREWEAR purchase.

Audio version

What the ancients knew about sunlight

The idea of getting morning sunlight was popularized over the last few years by Dr. Andrew Huberman1. He “considers viewing morning sunlight in the top five of all actions that support mental health, physical health, and performance.”

But Dr. Huberman isn’t the first to suggest that sunlight is essential for us.

Ancient cultures across the world—Egyptians, Greeks, many Native American tribes—believed the sun determined your health and happiness, and even used sunlight as a treatment for illness2.

Of course, ancient groups also had plenty of bad ideas, too, like humors, skinwalkers, and human sacrifice. So we shouldn’t romanticize the past. But sunlight has always spoken to humans, so it’s worth asking why.

The science of sunlight: circadian rhythms

In the 1900s, scientists began to study whether the ancients were onto something. They started researching “circadian rhythms”—24-ish hour biological cycles cued by day and night.

For example, when we open our eyes up to morning light, a few things happen34:

Our brains suppress melatonin, a “sleep chemical.”

A chemical called cortisol rises—it’s a healthy, short-lived rise that increases your alertness, focus, and immune readiness for the day.

Our internal clock starts a sort of “timer” to go to sleep 14 to 16 hours later.

I.e., Our bodies essentially recognize that it’s daytime and flip on “survive and function” systems. Later, they activate “prepare for sleep” mode.

How much does sunlight actually matter?

At the extreme end, we know that not getting enough sunlight will send you into a physical and mental spiral. Graveyard shift workers provide the best evidence of this56. These workers:

Have a higher risk of metabolic issues like obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Seem to have a greater risk of heart disease.

Have greater rates of mental health issues.

Graveyard shift jobs themselves probably contribute to those issues (e.g., being an overnight ambulance driver is sedentary, stressful, and probably at times depressing). But circadian disruption itself likely plays a role in the issues.

Most of us, however, live under the natural cycle of being awake in the day and asleep at night. So does morning light really matter for us?

Which brings us back to the claims on the internet—that you must get a certain amount of sunlight within a specific timeframe after waking.

A skeptical but charitable approach

If you’ve been reading Two Percent for long, you know I’m skeptical—almost to a fault. I look out across a sea of ultra-specific health information online and think a lot of it gets far ahead of the science and isn’t worth your limited time.

But morning light actually makes evolutionary sense. Humans evolved to wake with sunrise and sleep after sundown. Every cell in our body appears to have a tiny clock tuned to that cycle.

As Dr. Huberman put it—and I love this line—”[getting sunlight early] is not some woo biology thing. It is grounded in the core of our physiology.”

Lynne Peeples wrote a book called The Inner Clock: Living in Sync with Our Circadian Rhythms. It’s the smartest dive into circadian science I’ve found. She read all the research on the topic and spoke with all the key scientists.

I emailed Lynne about this topic. She told me:

Scientists widely recommend we seek light as soon as we can in the morning. Even just a dose of 15 minutes or so will help recalibrate your circadian clocks to get back in sync with the sun. Otherwise, our clocks are likely to drift a little every day. (They don’t tick precisely 24 hours a day.) Generally, getting that morning light sets your body up to fall asleep easier at night. It also helps align the trillions of clocks in your body so that they can optimally coordinate and regulate other physiological processes -- from metabolism to immune defenses.

She also added something important. “If you miss the morning light, it’s not too late! Some studies suggest that the most important thing is the total amount of light you see throughout the day.”

This suggests a hierarchy:

Worst: Getting no sunlight.

Good: Getting sunlight anytime.

Best: Getting sunlight within an hour or two of waking up.

Translation: morning is ideal, but sunlight any time beats none at all.

The sleep key

The Yale University sleep and circadian expert, Dr. Jade Wu, said7 that daily sunlight is essential mainly, “because that tells our circadian rhythms when it’s day and when it’s night. And the less confused it is about the timing, the better quality sleep and better quality.”

Morning sunlight won’t fix all of your problems. It won’t cure depression or lead your metabolism to burn with the heat of a thousand suns.

But if you’re sleeping poorly, it might help your sleep. And that’s likely the biggest benefit. Plenty of evidence shows better sleep reduces your risk of all sorts of problems—from obesity to diabetes to depression. For example, poor sleep is the leading risk factor for depression.

So if you sleep more:

You’ll likely eat less the next day, helping your weight status8.

You’ll likely be in a better mood9.

You’ll likely be able to focus and be more productive at work10.

The research backs this up, finding that getting sunlight (ideally early in the day) can for most people11:

Improve alertness.

Help us fall asleep faster later that night.

Improve sleep (fewer wakeups, etc)

How I think about morning sunlight

Let’s say this entire idea turns out to be wrong.

Well, who cares? You’ll only be out a handful of minutes, and you’ll still get many other good things by following it.

You’ll still get in some steps.

You’ll still get outside.

You’ll still get a few moments of quiet.

You’ll still spend 5-10 fewer minutes behind another damn screen.

Try this. It’s free and fast. If it helps you, keep doing it.

Walk outside for five to ten minutes in the morning.

Don’t wear sunglasses and (this should go without saying, but just in case) don’t stare directly into the sun. And you might want to stay out longer if it’s cloudy, according to Dr. Huberman.

Do almost nothing differently.

Notice what happens to your sleep.

Tracking will help you know if it actually helps.

And if you time it right, you can also get a hell of a show.

Which brings us back to my hike with Matt. Here’s what it was like:

Perfection. Then and there, I decided I’d try to watch more sunrises.

Perhaps more important than the long-term health benefits and complicated chronobiology is this: watching a sunrise is one of the best things ways to make life richer right now. And it’s even better if you do it with a friend.

Have fun, don’t die, see the light,

Michael

Levine, V. E. (1929). Sunlight and Its Many Values. The Scientific Monthly, 29(6), 551–557.

LeGates TA, Fernandez DC, Hattar S. Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014 Jul;15(7):443-54. doi: 10.1038/nrn3743. Epub 2014 Jun 11. PMID: 24917305; PMCID: PMC4254760.

Bowles NP, Thosar SS, Butler MP, Clemons NA, Robinson LD, Ordaz OH, Herzig MX, McHill AW, Rice SPM, Emens J, Shea SA. The circadian system modulates the cortisol awakening response in humans. Front Neurosci. 2022 Nov 3;16:995452. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.995452. PMID: 36408390; PMCID: PMC9669756.

Niedhammer I, Coutrot T, Geoffroy-Perez B, Chastang JF. Shift and Night Work and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: Prospective Results From the STRESSJEM Study. J Biol Rhythms. 2022 Jun;37(3):249-259. doi: 10.1177/07487304221092103. Epub 2022 May 3. PMID: 35502698; PMCID: PMC9149517.

Xi, J., Ma, W., Tao, Y., Zhang, X., Liu, L., & Wang, H. (2025). Association between night shift work and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, Article 1668848.

Thompson, D. (Host). (2023, April 25). The most important thing most Americans misunderstand about insomnia (Season 2, Episode 31) [Audio podcast episode]. In Plain English with Derek Thompson. Apple Podcasts.

Greer SM, Goldstein AN, Walker MP. The impact of sleep deprivation on food desire in the human brain. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2259. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3259. PMID: 23922121; PMCID: PMC3763921.

Triantafillou S, Saeb S, Lattie EG, Mohr DC, Kording KP. Relationship Between Sleep Quality and Mood: Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. JMIR Ment Health. 2019 Mar 27;6(3):e12613. doi: 10.2196/12613. PMID: 30916663; PMCID: PMC6456824.

Peng J, Zhang J, Wang B, He Y, Lin Q, Fang P, Wu S. The relationship between sleep quality and occupational well-being in employees: The mediating role of occupational self-efficacy. Front Psychol. 2023 Jan 27;14:1071232. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1071232. PMID: 36777224; PMCID: PMC9911531.

Anderson AR, Ostermiller L, Lastrapes M, Hales L. Does sunlight exposure predict next-night sleep? A daily diary study among U.S. adults. J Health Psychol. 2025 Apr;30(5):962-975. doi: 10.1177/13591053241262643. Epub 2024 Jul 30. PMID: 39077837.

I always laugh a bit when I see Huberman talk about morning sunlight. Not because I think its a silly endeavor but because I live in the Pacific Northwest... I've barely seen the sun in weeks and wont see much of it until maybe May. Makes me curious what native tribes in the NW have to say about sunlight exposure. Anyways I guess I'll turn my happy lamp up a bit extra today haha

As a huge fan of both Dr. Huberman and early morning light, I love this. I absolutely feel better after a few days of early light. Plus its free and harmless, so what's not to love?