Is exercise medicine—or is inactivity poison?

A conversation with exercise physiologist Brady Holmer.

Post summary

We’re running a sweeping conversation about fitness with Brady Holmer.

The central question we grappled with is, “Is exercise medicine, or is inactivity poison?”

The answers may change how you think about exercise so you can make better decisions and stay healthier longer.

Housekeeping

This post, like all Monday Two Percent posts, is free to all subscribers. Enjoy!

But only Members get full access to all three of our weekly posts and their audio versions. Become a Member below. One Member recently called Two Percent “the highest value on Substack. By far.”

ICYMI:

On Wednesday, we covered the five supplements I take and why (a common-sense guide).

On Friday, we ran a live AMA where I covered questions about gummy supplements, fasting, how to start rucking, an update on the podcast feed, and more.

Thanks to our partners:

Pro Compression created the official Two Percent sock for my 850-mile hike. I wear it nearly every day because it’s perfect. Get 40 percent off with code EASTER.

GOREWEAR designs endurance gear for Two Percenters. I live in their Concurve 2-in-1 Shorts during summer outdoor workouts. Use code EASTER for 30% off your next order.

Patagonia Provisions. Did you read our post on the power of small fish? Read it. Patagonia Provisions tinned fish are the original superfood. Use discount code EASTER15 for 15% off.

Audio version

The post

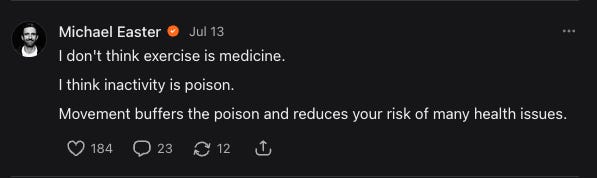

I recently posted this on Substack Notes:

Afterwards, Brady Holmer of the excellent Physiologically Speaking Substack reached out. “We should chat about this,” he said.

Brady studied human performance in grad school and is a wise mind in the exercise science space. He also practices what he preaches—he ran a 2:24 marathon in Boston this year.

I appreciate Brady because he deeply understands the science of exercise, but doesn’t get so caught up in the minutia that he can’t see out of it. He’s funny, smart, and practical—my favorite type of human.

Last week, Brady and I had a fun conversation that paired his physiology background with my evolutionary perspective on movement and philosophy of exercise.

Our edited conversation is below. In it, you’ll learn:

Whether exercise is medicine or inactivity is poison.

How the history of exercise research influences our understanding of exercise.

What a “normal” amount of exercise is for metabolic health.

How much exercise humans evolved to get (our evolutionary baseline).

What modern exercise misses about general health.

Whether standing desks and treadmill desks are “worth it.”

Why running injuries are so prevalent.

Whether “exercise snacks” are worth it.

The power of daily movement.

Whether cardio or lifting is more important.

Why too much exercise may have drawbacks.

More about the Two Percent mindset.

How to exercise when you have kids and a busy schedule.

Brady’s advice for people wanting to run or recover from a running injury.

I hope you enjoy the conversation as much as I did.

Michael Easter

This chat was prompted by me posting that exercise isn’t medicine so much as inactivity is poison. Given your exercise physiology background, how was the idea of exercise and health talked about when you were doing your academic work?

Brady Holmer

What drew me in was that this isn’t a topic you hear about often. I actually stumbled across it while reading some research articles by Frank Booth—a renowned figure in physiology and exercise—and later listening to a few of his conference talks. His work reframed how I thought about exercise.

In the field of exercise physiology, the common message is that “exercise is medicine” — and I agree with that. There’s a clear dose-response effect where more exercise tends to equal better health.

But Booth claims that physical inactivity itself is almost a disease state, and exercise isn’t just giving us extra benefits; it’s restoring us back to baseline. That framing really challenged the way I had been taught to think about movement and health.

It raises an interesting question: of course, exercise is good, but why is it good? Is it truly doing something special, or is it simply compensating for the way our modern environments keep us sedentary?

In other words, maybe exercise isn’t about giving us “extra” benefits but instead is just returning us to the natural state our bodies were designed for. You see this when looking at certain traditional populations. Some tribes show almost no signs of heart disease, yet they don’t necessarily “exercise” in the way we think of it. They simply live active lives. Our modern lifestyle is so inactive that we essentially have to schedule exercise to make up for what used to be built into daily living.

Michael

Part of me wonders if academia frames exercise as medicine because of the timing around when we started researching physical activity. The research on exercise began once we noticed that people who weren’t active were getting sick—so you're starting with a population that is rather inactive.

When these inactive people exercised, their health improved. That almost implied exercise is medicine.

Whereas if we started with, say, hunter-gatherers who were highly active you’d just think exercise was normal. If you noticed that the inactive ones were getting sick, that would change your perspective, and you might assume inactivity is poison.

Brady

A couple of years ago, I came across a paper by Iñigo San-Millán — he’s been on Peter Attia’s podcast and is credited with popularizing the Zone 2 exercise discussion.

He raised an important question about how we design exercise science studies. Typically, these studies recruit people who are not regularly active. They’re not meeting the 150 minutes per week exercise guideline. Researchers usually avoid using highly trained athletes because it’s harder to see improvements when people are already near their ceiling.

San-Millán argued that maybe our control groups are the problem. If you always compare exercise interventions to inactive people, of course you’ll find big improvements — you’re basically taking people who don’t exercise, giving them exercise, and watching them get healthier.

But what if we used fit, active people as the control group instead? For example, people who already exercise 300 minutes a week and exceed the guidelines. That shifts the question to how much additional benefit does a training intervention provide beyond an already active lifestyle?

Some of the research he and others have done shows that even people we’d consider “healthy” (normal BMI, reasonably active) still display signs of mitochondrial dysfunction compared to those exercising more. In short, they looked metabolically unhealthy despite seeming “fit enough.”

That aligns with broader data showing that only around 12% of Americans meet ideal cardiometabolic standards. San-Millán’s point was that our definition of “normal” is skewed. Going to the gym twice a week for 30 minutes isn’t “active” at all. It’s inactive, even though society tends to see it as good enough.

Michael

That tracks with history. The studies on hunter-gatherers suggest that for most of time, humans took anywhere from 10,000 to 20,000 steps a day.

But we also forget there’s so much other physical work they do. For example, they’re carrying tools and food as they walk. They might occasionally jog. They might have to squat and dig for tubers or climb a tree for honey.

They’re also using their brain the entire time—tracking animals and navigating so they don’t get lost. They really have to think as they move, and I think modern exercise often removes the cognitive element.

Even their sedentary time isn’t as sedentary. David Raichlen’s work shows that hunter-gatherers are just as sedentary as we are, but they don’t plop down into supportive chairs. They squat or sit on the ground, which requires more moving and low-level muscle activity.

Most research suggests they mostly avoid most of the chronic diseases we do, like type 2 diabetes, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, etc.

Brady

In modern life, you can go almost an entire day without really engaging your core or supporting your own body. If I’m sitting in a chair, leaning back, my abdominals aren’t doing anything. Even sitting on the ground requires more postural stability than most of what we do throughout the day.

So it makes me wonder: does the type of sedentary behavior actually matter?

When standing desks became popular a few years ago, they were often pitched as a solution to the whole “sitting is the new smoking” idea. But is there really any evidence that standing all day is better than sitting?

Michael

I think there are multiple ways to look at it.

For one, research that compares the calorie burn of sitting versus standing finds there isn’t much difference. But that happens in a lab, and in real life no one remains totally stationary when they stand—they shift around more and fidget more, so those studies probably don’t capture that. Now, does that matter? I don't know.

Second, I think a standing desk might improve movement quality. For example, a standing desk might help you avoid tight hips and weaker glutes. And that could potentially help active people avoid injuries over the long run.

Have you ever used a treadmill desk?

Brady

I just can’t do the treadmill desk thing. If I’m reading or typing, I have to be sitting. You’d think I’d be all for it — walking while working sounds great in theory — but for me, it makes it harder to focus. Plus, I don’t really want more activity than I’m already getting.

That said, I think it’s awesome for people who can make it work, especially for things like meetings. The only downside is the noise. Ben Greenfield actually tried podcasting while walking on a treadmill desk, and you could hear the thump of every step in the background. I remember thinking, this is terrible. Please don’t do this while recording!

Michael

I haven't used a treadmill desk, but I will say my wife, Leah, can work and use one. She'll get like 30,000 to 40,000 steps a day some days. It's crazy. It's wild. I wrote a post about it called “My wife: the insane walker.”

Brady

If you’re doing that over a six-to-eight-hour workday, damn, you could rack them up.

Michael

She definitely racks them up.

Related to this topic, I’d like to hear your take on running injuries. The data is all over the place, saying something like 20 to 80 percent of runners get injured each year. Do you think inactivity during the day influences running injuries?

Brady

I do think the lack of movement in daily life can contribute to issues, and I’ve felt this personally. Obviously, that’s just anecdotal, but sitting all day definitely gave me tight hip flexors in the past.

A common scenario is someone working at a desk for eight hours, then heading straight out for a run or workout. You’ve been stiff and immobile all day, and then you’re asking your body to perform without much of a warmup — that can absolutely increase the risk of injury.

Postural weakness plays into this too. Sitting all day can mean weaker glutes or weaker support muscles in general. The good news is that proper strength training can offset a lot of this. I don’t think inactivity alone dooms you, as long as you’re diligent with movement breaks, stretching, and building strength.

For runners in particular, it’s important to pay attention. Whether you run in the morning and then sit all day, or you sit all day and run in the afternoon, you’ll feel the effects. Even I notice that if I go straight from a run to sitting for a few hours, I feel awful when I stand back up. As we get older, these things matter more.

Michael

From an evolutionary perspective, that tracks with me. I believe several factors have contributed to slightly higher injury rates when we run (or do other forms of exercise).

For one, as you pointed out, all the chair sitting.

Second, we’re much bigger people today due to advances in nutrition. And that probably factors in. You’d know the data better than I would. But it seems reasonable to me to say that, height and all other things equal, a 130-pound person is less likely to get injured than a 230-pound person.

Brady

Yeah, definitely. I think about knee issues in particular — carrying extra weight puts stress on the joints in a way the body probably wasn’t designed to handle.

That makes me wonder: do we have any records of injury prevalence in hunter-gatherer populations? Do we know how often they get injured, and if their injuries are similar to what we see today?

They’re obviously doing hard physical work — lifting, carrying, moving all day — which you’d think could raise the risk of injury. But when they’re carrying something heavy, like a pail of water, are they getting hurt doing that? Or do we just not really have data on this?

Michael

I'm sure you're familiar with the book Born to Run. It covered running among the Tarahumara tribe in Mexico. The author said they never get injured. That’s not true.

The Harvard anthropologist Dan Lieberman attended one of their events, where they run long distances kicking a ball. I’m talking like 50 miles during a game.

Afterwards, he noticed a lot of the runners hobbling around. Many of them were complaining, saying “I am sore as hell,” “my knee hurts,” blah, blah, blah.

At the same time, the the injury rate among hunter-gatherers is probably lower than it is among active people in the U.S., for differences related to relative strength, body size, mobility, and more.

Brady

What’s interesting is they're not training. They just do a big run one day.

That would be like signing up for a marathon, not training, and then running it as hard as you can. You’ll probably get injured no matter who you are.

Ed Coyle, a researcher at the University of Texas, has done some fascinating work on the importance of activity outside of training. He coined the term exercise resistance, and I’ve even written a couple of blog posts about it.

The basic idea is that even if you’re training hard — say 60 to 90 minutes of exercise a day — what you do the rest of the day still matters.

A lot of us think, “I did my workout this morning, now I’ll just recover by sitting around.” But Coyle’s research shows that background physical activity plays a crucial role in maximizing training adaptations.

In some of his studies, people would do a workout — either resistance or aerobic training — and then consume a high-fat meal, like a milkshake. Researchers measured their postprandial responses (glucose and blood lipids after the meal). One group was required to get about 7,000 steps per day in addition to their training, while another group was restricted to fewer than 2,000 steps — essentially forcing them into a sedentary pattern. Those with limited movement had worse metabolic responses to the meal, even though they did the same structured training.

They’ve also found similar effects with outcomes like fitness and muscle strength.

The takeaway is that if you’re sedentary outside of your workouts, you’re not getting the full benefit of that training. That’s what Coyle calls exercise resistance. Low-level physical activity throughout the day helps your body fully adapt and respond.

This has definitely changed how I think about training. Obviously, if you’re doing something extreme like Ironman-level workouts, resting on the couch is fine. But for most people, it’s not enough to just check the “training” box — you also need to stay active the rest of the day. Otherwise, you can still be what we’d call “physically active” yet remain metabolically impaired if you’re sedentary outside those workouts.

Michael

That tracks with the data on NEAT, which is activity that isn’t exercise. The average American burns more calories a day from NEAT than exercise.

I think it also raises questions about how we view exercise. We engineered the world so we don’t have to be physically active for work and to survive. But once we stopped moving, we started getting sick. So the message became “do this special movement for 30 minutes a day, we’ll call it ‘exercise.’” But we didn’t do as great of a job promoting movement throughout the day, outside of our special exercise period.

Exercise is great. But I do think we need to ask ourselves, “how can I move more throughout the day?”

Brady

I was out on a run the other day and couldn’t help but laugh at the concept of exercise. I wake up, lace up my shoes, and go beat myself up for an hour — not because I have to, but just because that’s what I do. Don’t get me wrong, I love it, but it is kind of strange when you think about it. Exercise as this structured, dedicated block of time is such a modern invention.

What if we scrapped the whole idea of “purposeful” exercise and instead shifted back toward a hunter-gatherer model of just moving constantly throughout the day without needing to schedule a workout?

Obviously that would improve health since people would be more active, but do you think that could actually be a more effective intervention than telling people to exercise? Because as we know, structured exercise carries all kinds of barriers that make it hard for people to stick with.

Michael

Well, I think it would take overhauling the system, which is probably not desirable.

But I will say, when you look at people who farm for a living and don’t use modern farming technology, like the Amish, they eat a pretty heavy diet, and their health is surprisingly great because they’re moving all day.

They’re strong as shit. Their endurance is pretty good.

The farming life sounds quite idyllic as I sit in my office. I’m sure the reality is much harsher. Like, 100 acres with cows and goats sounds great until you have to keep the cows and goats alive every damn day. I’ll take writing behind a desk. There’s a very clear reason we ended up where we did.

Brady

The research on “exercise snacks” is pretty interesting and almost supports the idea of moving constantly throughout the day. Things like movement snacks or vigorous intermittent activity show that you don’t necessarily need to carve out a big block of time — you can just sprinkle bouts of exercise-like movements throughout the day, and those seem to have real benefits.

My question, though, is whether those benefits only apply to people who are extremely inactive.

Do exercise snacks actually improve fitness in someone who’s already training regularly? For example, would I personally get fitter by adding in exercise snacks throughout the day? Maybe — it probably wouldn’t hurt — but do they make a meaningful difference beyond a structured training routine?

Michael

I think it depends on the context and where a person is at. Basically, the less active you are, the more exercise snacks help.

Take you. I know you didn’t used to lift weights, but have started lifting more.

Before you started lifting, I imagine some pushups, planks, squats, lunges, etc, between meetings would have meaningfully improved your strength.

Brady

A lot of my resistance training now actually looks like exercise snacks. I’ll just keep a dumbbell next to my desk and knock out some presses or lifts during the day. For me, it’s often easier to fit that in than trying to make it to the gym.

Michael

You have a running background. I was an editor at Men's Health for a long time, so that gave me more of a strength background. I do think in the lifting sphere, people get too caught up in getting strong for the sake of it—chasing numbers.

At a certain point, we become strong enough for health and general preparedness, and trying to become even more strong won’t help health much and could be disadvantageous. And that’s because, once people start chasing numbers, they tend to get injured.

Do you see that in the running world?

Brady

You’ve written about VO₂ max, fitness, and longevity, and I agree there’s definitely a point where pushing VO₂ max higher doesn’t necessarily translate to a longer life.

It may help performance, sure, but if we’re just talking about maximizing health, I don’t think anyone needs a VO₂ max of 80. Somewhere in the 60–65 range probably still carries benefits, but beyond that, you start to see diminishing returns. And if you’re chasing that number to the point of running yourself into the ground, it could even become counterproductive.

I’m always curious about where that balance lies. We talk a lot about wanting both aerobic fitness and strength, but in my opinion — and I’ll admit I’m biased as a cardio junkie — the level of strength needed for health and longevity is probably a lot lower than the level of cardiovascular fitness.

You need a baseline amount of strength to function day-to-day, avoid injury, and handle basic activities. But when it comes to VO₂ max, I feel like you can push that number higher before hitting diminishing returns.

Do you see it the same way? Or do you think strength and aerobic fitness plateau at similar points when it comes to their impact on longevity?

Michael

I would agree that endurance is probably more important than strength. I think people need to be strong enough, but those numbers are not crazy. You probably start to hit a diminishing rate of returns on strength faster.

If you look at it from an evolutionary context, we evolved more as endurance athletes than we did being super strong. When you look at what hunter-gatherer tribes lift across the day, they're rarely lifting anything more than 20 pounds. No one who has to lift for work tries to lift the heaviest thing.

I’ll also say, with you talking about chasing VO2 max and me about chasing strength, bigger questions are worth asking.

If your VO2 max and strength are good enough, if your goal is health, you might be better off spending your time doing other things.

For example, making more money for better health insurance or to buy better food. Or spending more time with friends and family. There are various buckets that need to be filled to live well and long, and exercise is just one bucket.

Brady

Yeah, that’s interesting — kind of a philosophical point. I’d agree that if you’re already training, say, ten hours a week, the question becomes whether those extra five hours are really worth it. Of course, it depends on your goals. If you’re training for something like an Ironman, then yes — you’ll probably need those extra hours just to finish or perform well.

But if we’re talking purely from a health-optimization perspective, maybe those five hours would be better spent elsewhere, like getting comprehensive blood work, investing in better food, or even focusing on recovery.

I don’t think it’s a hard argument to make. You’re probably right that, for most people, the marginal gains from more training aren’t as valuable as improvements in other areas of health.

Michael

Right. And I think in some cases, when people get overly focused on training, it can slip into a kind of neurosis. It’s like the obsession itself becomes unhealthy, especially for mental health. But at the same time, I wonder if that’s just the type of person we’re talking about. Maybe if they weren’t obsessed with exercise, they’d be obsessed with something else.

Brady

You see that a lot with ultra-endurance athletes. Some of them come from backgrounds of addiction — maybe drugs or alcohol — and then they find ultra-running as a replacement. It fills that same void in a different way.

Michael

It's such a complex thing once you start to unpeel the layers.

But going back to the big picture, we know we need to move. We know we need to move significantly more than the average person is moving today. But then once you've moved enough, the benefits start to decline. And you see that in all the data.

Brady

When it comes to steps, I think the benefits level off much farther down the road than we sometimes assume. Some of the recent studies suggest around 7,000 to maybe 10–12,000 steps per day as a sort of upper limit for health benefits.

For me, the key message is simple: move more, especially in ways that mean you’re sitting less. Going back to that idea that inactivity is uniquely harmful, the more you can replace sitting with low-intensity movement, the better. And honestly, I don’t think there’s really a ceiling when it comes to the benefits of light activity. The more of it you can work into your day, the more it supports your health.

Michael

This is why I always harp on that 2% concept. 12,000 steps is probably an extra hour walk in your day if we assume you get 5,000 steps just living life. That’s a significant time commitment.

And so how do you find that time? Well, if you have a work phone call, take that phone call while you're out walking. It beats sitting. Get creative with it.

Brady

Maybe I’ll wrap up with one last question for you. You’re kind of the strategies-and-hacks guy, so if someone says, “I want to be less sedentary,” what are the top three things — either from your own life or from your research and writing — that you’d recommend they implement? In other words, what are the most practical, effective things people can do to sit less and move more?

Michael

The big picture is figuring out ways to make what you’re already doing a little more active. Take the stairs, take calls while walking, park as far away as possible, walk the terminals while you wait for a flight, use the basket at the grocery store.

No single one of those things done once will change your life. But collectively, done at every opportunity, they probably will.

Brady

I think if something becomes a slight inconvenience, that’s almost a good thing — it forces you to do the thing that’s a little less comfortable. I love the airport example. Whenever we’re traveling with my son, my wife might want to sit in the lounge, but I’ll volunteer to carry him and just walk circles around the terminal while we wait.

Honestly, it feels better. Once you get in that habit, it’s preferable — I’d much rather walk around listening to an audiobook than sit in an uncomfortable airport chair, people-watching.

And the walking meetings. I think those are all great strategies — and the best part is they don’t require a ton of extra effort.

Michael

My final question for you is, you have a kid, you just moved, you have a job that requires a lot of work. What’s your advice for helping people fit in dedicated workouts?

Brady

It really comes down to time management. Sometimes it just means waking up earlier than usual. Having a supportive spouse helps too — we’ll trade off. For example, I’ll cover the afternoon routine, and she’ll take the morning shift, which is when I get my workout in. Early on, when my son wasn’t in school yet, that was especially important. I’d be home with him during the day while my wife was at work, so if I didn’t train first thing in the morning, it just wasn’t going to happen.

Working out at home has also been huge. If your kid naps for a couple of hours, that’s the perfect window to hop on a treadmill or bike without having to leave the house. And then there are the things you can do with your kid. Running strollers have been a game-changer — I can go out for a two-hour run, and my son is perfectly content in the stroller with a snack, just taking in the world around him. Same with the bike trailer. He loves the ride, and I get my workout in.

So for me, it’s really about integrating exercise into family life. You don’t always need a “hack” — just good time management, creativity, and a partner who supports your training.

Michael

I lied. I have a final-final question: What’s your advice for people who want to start running or get back into running?

Brady

My top piece of advice is: don’t be afraid to use the run-walk method. A lot of people feel like they need to run two or three miles straight, or at least 10–15 minutes without stopping. But even after almost two decades of running, whenever I’m coming back from an injury, I always use run-walk.

The concept is simple. Run for a set amount of time — maybe just a minute to start — then walk, then run again. Think of it like an interval workout. The runs are your intervals, and the walks are your recoveries. Over time, you just increase the amount of time you’re running, while keeping the walking breaks the same. Eventually, those walk breaks get shorter and you’re running continuously for five minutes, then ten, then more.

The beauty of this method is that you can still go out for an hour or two, but maybe only 30–40 minutes of that is actual running. It breaks things up so your body isn’t under as much stress, which lowers injury risk and allows you to gradually build fitness.

I use it all the time, and I even recommend it to experienced runners. It’s such a simple way to add low-intensity volume, build consistency, and reduce the intimidation factor that often comes with starting or restarting running.

Have fun, don’t die, move,

Michael

Brady’s and Michael’s Substacks are my favorites — and the only ones I pay for. And now you both posted the same content at the same time 😂 Love it! Thanks for the amazing work!

Fantastic convo between two of the best sources of common sense fitness knowledge out there.