The New Science of the Two Percent Mindset

We used to think 1 minute of hard work equaled 2 minutes of moderate work. The new math blows that up.

Thanks to everyone who filled out my survey last week. We’re working on sharing the results (and some announcements). Fill out the survey here if you haven’t already. You’ll help make Two Percent better than ever.

For years, exercise scientists believed that vigorous exercise is about twice as powerful as moderate exercise. It’s why the federal exercise guidelines1 tell us we can do half as much movement if it’s vigorous:

(A)dults should do at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity.

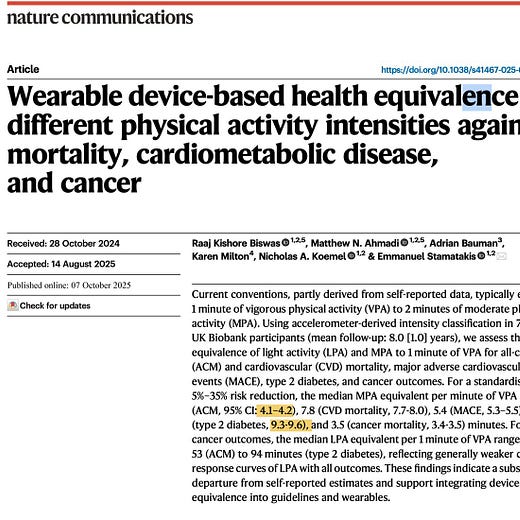

But a few weeks ago, a study published in Nature Communications2 called that math into question.

It also led to the internet exercise dork equivalent of The Real Housewives: Drama, in-fighting, name-calling.

We’ll get to the drama. But I’m not as interested in online weeping and gnashing of teeth as I am in what the study actually found.

The new work reshapes how we should think about the Two Percent mindset: finding opportunities to embrace short-term discomfort to get long-term benefits.

I’ve argued that we’d all be far healthier if we moved more in daily life. And I’m not talking about exercise.

I’m talking about making life more active: Take the stairs instead of the escalator. Park in the farthest spot. Take a phone call while walking instead of sitting.

This study shows us how to make those moments even more powerful. If you follow its advice, the data suggests you’ll be less likely to get heart disease, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, have a stroke—or die from any cause.

Here’s our roadmap:

Why the old 2-for-1 exercise rule is likely wrong.

The internet drama between a best-selling author and running coach (and who is actually right).

The new exchange rate of exercise: Exactly how much time you save by going harder.

Three specific ways to apply and amplify Two Percent mindset to get these benefits.

Let’s roll …

Quick housekeeping

In case you missed it:

On Wednesday, we covered the Best Fitness Advice I Ever Got From Olympians—10 lessons on durability, engine building, and why you should never do fasted cardio.

On Friday, our Expedition post dropped 21 new ideas to make you smarter, healthier, and wealthier this month (it was a favorite for many of you).

Shoutout to our partners:

Run forever with Janji, an independent running brand making gear built for ultra-distance pursuits. They’re the only brand making gear specifically for 200-plus-mile adventures—my favorite kind. Check out the Circa Daily Long Sleeve, great alone or as a layering piece. Find Janji at Janji.com and at REI stores nationwide.

Function Health, which offers 5x deeper insights into your health than typical bloodwork. You’ll learn critical information that can guide you into feeling better every day. It helped me identify a mineral insufficiency. Go to my page here to sign up, receive a discount, and pay just $340.

The Study and What it Found

Researchers in Australia and the UK pulled about 73,000 participants—average age 61 and all healthy at the start of the study—from the UK Biobank.

The UK Biobank is a massive long-term health database tracking the genes, medical records, and lifestyles of about 500,000 people. It helps scientists study what actually drives disease, aging, and longevity in the real world.

The participants then wore wrist-worn accelerometers 24/7 for seven days.

Accelerometers are different than everyday fitness trackers like FitBit or WHOOP, which guess intensity based on your heart rate. Accelerometers measure your physical acceleration in space. Basically: if you’re running, the device senses that you’re moving faster (high-intensity movement). If you’re sweeping the floor, it moves slower (low-intensity). They also don’t have screens, so participants don’t get feedback that changes their everyday behavior.

The devices categorized movement into three buckets:

Light intensity: Walking around the house, doing dishes, light chores.

Moderate intensity: Yard work, walking briskly, climbing stairs.

Vigorous intensity: Anything that elevates your heart rate and breathing substantially. This could include high-intensity intervals, but also jogging. Even walking at a 15-minute-per-mile pace qualifies for older adults.

That week’s worth of data gave researchers a sense of how active the participants were in their daily lives.

The researchers then followed the people for eight years. They looked at who died, who got heart disease, who got cancer, who got type 2 diabetes, etc.

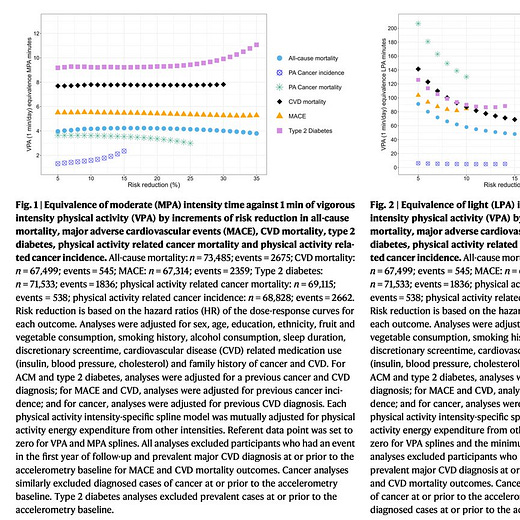

If two minutes of moderate activity is equal to about one minute of vigorous, the people who did more vigorous movement should have gotten the same protection in half the time.

But that’s not what happened. They got multiples more than that. For reducing the risk of disease and death:

One minute of vigorous activity was equivalent to 4-9 minutes of moderate activity.

One minute of vigorous activity was equal to 53-156 minutes of light activity.

I.e., the old math got nuked.

Why we were wrong

The old 2:1 ratio—2 minutes of moderate activity = 1 minute of vigorous—came from studies in which people self-reported their activity.

The problem: people generally only remember and report “structured exercise” (blocks of time specifically set aside for working out). They miss all the Two Percent stuff: the movement they do across a day, like hustling up a few flights of stairs.

By using wearables, this study captured the Two Percent stuff that questionnaires miss.

In short: This study was powerful because it captured every minute of movement regardless of intent—concluding that the intensity of the movement matters more than whether it was formally considered “exercise.”

Intense Movement: An Evolutionary Necessity

For nearly all of time, survival required moving hard often. This movement could have come from a jog while hunting, or carrying a heavy water pot uphill.

Today, we move about 14 times less than our ancestors3. And when we do move, it’s light stuff: walking from the couch to the fridge, pushing a shopping cart, standing at a desk.

We can survive today without ever moving more intensely—and that is a very new thing for our bodies. It opens the door for disease.

I talked to Brady Holmer of the great Physiologically Speaking Substack about this study for an upcoming project (get excited).

He told me previous studies support the new conclusion: “In randomized controlled trials run by Martin Gibala, they’ll have a high-intensity interval training group do, say, 10 minutes of intervals, and they’ll improve their VO2 max or blood glucose or insulin sensitivity the same amount as a group doing 40 to 60 minutes of moderate exercise,” Brady said. “So there’s some good synchronicity between that work and this study, which makes me think it’s legit.”

Disagreements on the Study

The study came on my radar thanks to internet drama.

When the paper dropped, Black Swan author and statistician Nassim Taleb shared it on Twitter. He argued it proved high-intensity training is better than easier Zone 1 and 2 exercise for everyday people:

Running coach and author of Win the Inside Game, Steve Magness, fired back, saying Taleb is “making a big mistake interpreting this paper.” He responded to Taleb with a Subtweet, writing a long post. Here’s the gist:

This paper doesn’t test zone 1-2 vs. 3-5 or easy vs. intense exercise …

The actual findings of the paper: any type of exercise, be it easy or hard is more efficient than a slow walk, at providing health benefits.

Great. No brainer. But it says nothing about whether a slow jog is better or worse than some hard intervals. It doesn’t test this. Even though folks are quick to try to say it does.

All it says is: what nearly everyone would define as exercising is better than casual movement.

Taleb then called Magness “a bro-science (R-word).” Magness wrote a full Substack rebuttal, then recorded a 20-minute YouTube video.

So who’s right?

Taleb is right in the sense that this study implies exercise in zones 3 to 5 (harder) is more powerful than zones 1 to 2. That’s not what the study actually looked at—but it’s a defensible extrapolation for the “vanilla citizen,” as he put it.

Magness is right in that the study didn’t look at exercise zones, and that this study would have likely put what most consider Zone 2 into the “vigorous” category.

They’re each wrong in the sense that—in their Tweets—they’re talking about “exercise.” The study used the word “exercise” 5 times, mostly when discussing what previous studies found. On the other hand, the study used “physical activity” over 100 times—hammering the point that the scientists were really trying to figure out the health impacts of all the incidental movement we do throughout the day.

But for most of us, the debates are a distraction.

What the Study Means for You

The good news: You don’t need a PhD in exercise physiology to act on this. You don’t need to argue about training zones on Twitter or take a side.

You just need to close the gap between how your body evolved to move and how the modern environment has changed that.

1. Amplify the Two Percent mindset

The study tracked people in real life, not in labs. The “vigorous” movement that mattered wasn’t always structured exercise. A lot of it was life, lived slightly harder.

This is exactly what we talk about when we talk about the Two Percent mindset.

But as the flaws in the previous research show, we totally forget about these moments. Yet they’re exactly what we need. They give our bodies the brief, more intense signals they evolved to need and that modern life engineers out.

The study also shows us how to make the Two Percent idea more powerful.

It suggests you’ll get even more benefits if you dial up the discomfort of your everyday movements. That is to say:

You get an A for taking the stairs—and an A+ for hustling up them.

You get bonus points for parking far away, and bonus-bonus points for walking fast across the lot.

You win the battle by taking phone calls while walking—and the war if you toss on a light ruck each time.

2. You don’t need as much time as you think

The study suggests that if you’re short on time—and we all are—you shouldn’t feel bad if you can’t carve out an hour for a workout. Find moments throughout your day where you can move harder than normal.

In the study, one minute of vigorous movement equaled 4 to 9 minutes of moderate movement (and more than 56 minutes of light movement).

If you’re time-constrained—or have a day when you planned to go to the gym, but life intervened—just find a handful of opportunities that day to move quicker.

3. Make your steps more powerful

The study suggests 10,000 steps of slow walking is not the same as 6,000 steps that include bursts of speed. The second option, this study suggests, is better for your health and takes less time.

As Brady Holmer put it:

All steps are not created equal. If you get 10,000 steps that are vigorous versus 10,000 steps that are moseying around the house, those are vastly different in terms of how those are going to impact your health. I think it’s reassuring for people who find it hard to get 10,000 steps. You have to walk for 1.5 to 2 hours a day to reach 10,000 steps. So if you can’t get it, do brief, vigorous bouts where you’re walking fast across a parking lot or hustling up stairs. Those actually have a big impact on your health.

Have fun, don’t die, move more, move harder,

Michael

Audio Version

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2018). Physical activity guidelines for Americans (2nd ed.).

Biswas, R.K., Ahmadi, M.N., Bauman, A. et al. Wearable device-based health equivalence of different physical activity intensities against mortality, cardiometabolic disease, and cancer. Nat Commun 16, 8315 (2025)

Raichlen DA, Pontzer H, Harris JA, Mabulla AZ, Marlowe FW, Josh Snodgrass J, Eick G, Colette Berbesque J, Sancilio A, Wood BM. Physical activity patterns and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk in hunter-gatherers. Am J Hum Biol. 2017 Mar;29(2). doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22919. Epub 2016 Oct 9. PMID: 27723159.

This is really interesting and your interpretation is great. As a super busy parent with a busy job, I’m very lucky if I can carve time at the end of the night for even a 30-60 minute workout. But what I do every single weekday is make sure to go walk between meetings (and throw a ruck on), fit in little bursts of kettlebell swings, a quick push up circuit, and the run crazy with my kids at the end of the day. Great to hear that it’s being reinforced that these little moments make a difference in health.

It is ironic the people creating the drama have next to nothing to do with the benefits of getting after it physically. I'll take sprinting up the stairs over the noise. Great piece, Michael.