A New Study Just Flipped What We Thought About Exercise and Calorie Burn

Four ways to use the study to reach your goals.

You’ll learn:

For years, scientists have debated whether exercise really increases how many calories you burn in a day.

A new study adds clarity—and might change how you think about movement, fat loss, and performance.

We’ll cover how this study challenges a groundbreaking finding from 9 years ago and how you can use its findings to reach your goals.

Housekeeping

This post, like every Monday post, is free to all subscribers. But only Members get full access to all three of our weekly posts. Become a Member here:

ICYMI:

On Wednesday, we explored the new science of habits and 18 ways to break bad habits and build good ones.

On Friday, I explained why a world record powerlifter told me not to bench press and the best d*mn upper-body exercise on earth.

Audio version

The post

The Harvard researcher Daniel Lieberman once joked, “If you want to start a fight in a room of exercise scientists, shout loudly, ‘Exercise doesn’t help you lose weight!’ then run.”

That fight has raged for decades. Do you actually burn more calories when you move more? Or does your body find sneaky ways to even things out?

A new study offers clarity—and might change how you think about movement, metabolism, and performance.

The classic view: The additive calorie burn model

For decades, we thought that the calories you burn through exercise add to the total calories you burn daily. Burn 500 calories on a run, and you’ll burn 500 more calories that day.

If you just exercise enough, you can burn more calories than you eat and, in turn, lose weight. Straightforward math—or so we thought.

The twist: The constrained calorie burn model

In 2016, Duke researcher Herman Pontzer challenged that simplicity.

He studied1 the metabolism of the Hadza hunter-gatherer tribe in Tanzania. They’re about 14 times2 more active than people living in modern environments.

Pontzer found that the highly active Hadza didn’t burn any more calories across a day than relatively sedentary Westerners. Pontzer wrote in Scientific American:

When the analyses came back from [the lab], the Hadza looked like everyone else. Hadza men ate and burned about 2,600 calories a day, Hadza women about 1,900 calories a day—the same as adults in the U.S. or Europe. We looked at the data every way imaginable, accounting for effects of body size, fat percentage, age and sex. No difference.

He calls his findings the “constrained energy hypothesis.” Here’s how it works:

Our bodies run on a relatively fixed calorie-burning budget.

If you exercise, you’ll burn some calories.

But then, quite deviously, your body works some internal magic and burns fewer calories elsewhere.

For example, your metabolism drops and you also unconsciously move less throughout the day, compensating to balance the books.

The overall effect: You end up at around a net zero and don’t lose weight. Pontzer summed it up in his book, Burn:

The bottom line is that your daily (physical) activity level has almost no bearing on the number of calories that you burn each day.

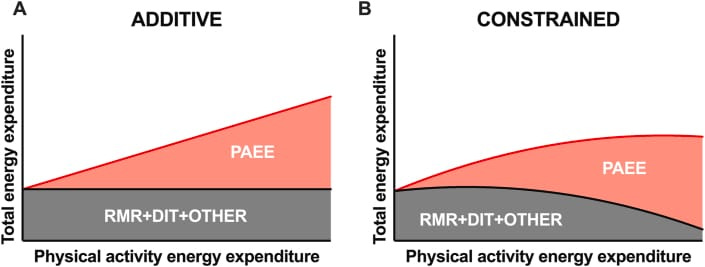

The graphs below can help us visualize the two ideas.

Graph A shows the “Additive” model. Graph B shows the “Constrained” model.

Each displays your body’s non-exercise/metabolic calorie burn in grey and your exercise calorie burn in red.

Notice how in the constrained model, your daily non-exercise/metabolic calorie burn drops as your exercise burn goes up, capping the number of calories you’ll burn across a day.

Pontzer’s study and book were a bombshell. Major media outlets and podcasts championed the idea, changing public messaging around exercise and calorie burn. Two Percent covered his theory here.

The new paper: The additive model strikes back

On October 21st, a study was published in the The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS)3. Its title:

It suggests the old idea was right after all and that the constrained theory is wrong.

The research wasn’t from academic lightweights. John Speakman, one of the authors, is a pioneer in the field of energy metabolism science. He literally helped develop the measurement methods used in these studies.

How the study was conducted and what it found

The scientists measured the daily calorie burn of 75 healthy men and women in Virginia, aged 19 to 63. Some were sedentary, others exercised a few times a week, and others were hardcore ultra-runners.

Over the course of two weeks, the scientists tracked the participants’ physical activity levels, diets, health markers, and calorie burn using the doubly labeled water method.

The findings: The more people moved, the more calories they burned.

There was no sign of compensation.

No slowdown in metabolism4.

No drop in biological processes, like immune function or reproductive markers.

Notably, the most active participants actually spent less time sitting5.

Note that the study didn’t directly measure weight loss or athletic performance, but its findings could have implications for how we think about those two topics.

Could both models be true?

On one hand, we have strong data from Pontzer supporting the constrained model.

On the other hand, the new PNAS paper strongly supports the additive model.

How can two rigorous studies from top researchers show opposite results?

Greg Mushen offered a smart explanation, which Speakman seemed to agree with.

The different findings may come down to differences between the study participants—their environment and general health.

Pontzer’s work examined subsistence populations such as the Hadza hunter-gatherers, who often live with constant immune challenges from parasites, wounds, and infections.

The new PNAS study examined healthy Westerners in Virginia who had access to clean water, ample food, antibiotics, and low exposure to pathogens.

Here’s the key: When your immune system is fighting infections or healing injuries, it becomes energy-hungry.

Studies show that this state can raise daily energy expenditure by roughly 300–500 calories.

So both models might be right—depending on the setting.

In subsistence populations, a significant portion of calorie burn gets diverted to immune defense. There’s less energy left to scale up activity—so their metabolism looks like a constrained pattern, even though they move frequently.

But in healthy modern populations, where infection is low, there’s no big “immune tax.” The body has no reason to limit its total energy use. Their bodies freely ramp up energy burn as they move more—and the additive model wins.

What this means for you

1. Be a Two Percenter

The new study suggests that in healthy people, movement really does add up to more calories burned throughout the day.

But the larger problem is how society views movement. We “exercise.” We see movement as a special and distinct event that isn’t part of everyday life. It’s our 30-minute run or trip to the gym.

Once our special “exercise” moment is complete, we’re sedentary the rest of the day—and this limits our health and calorie burn.

Our daily movement that isn’t exercise—which scientists call NEAT—is extremely powerful. Research suggests that the average person burns far more calories a day from NEAT than they do through exercise. Mayo Clinic researchers say6 that NEAT can add up to 2,000 extra calories burned across a day.

The takeaway: Be a Two Percenter. Don’t just work out. Actively seek ways to add more movement back into your daily life. Walk, carry, fidget. It all adds up. If you’re unfamiliar with the Two Percent mindset, read more on the idea here.

2. To lose weight, manage what you eat as you move more

On Twitter, I wrote the following about this finding:

The new PNAS study shows exercise can help you burn more calories. But exercise alone probably won’t help you lose weight if you don’t control what you eat.

Consider the DREW study7. It had women walk either 0, 70, 140, or 210 minutes a week. We’d all assume the women who walked the most lost the most weight.

But that’s not what happened. After six months, the women who walked 140 minutes a week lost an average of five pounds. But the women who walked 210 minutes lost only three pounds.

Why? The women who walked more ended up eating more. Various studies have found that as we reach higher activity levels, hunger typically increases and we end up eating more, which offsets weight loss.

But if we monitor our eating and don’t eat more as we move more, we’ll likely lose weight. (This is easier said than done.)

3. To boost performance, eat enough as you move more

More movement means more burn—but also higher fuel needs. If you’re training hard (rucking, hiking, lifting), under-fueling slows recovery, blunts adaptation, and raises injury risk.

I learned this on my 850-mile hike. I was eating about 5,000 calories a day, but lost 15 pounds. Pontzer did some back-of-the-hand math and told me I was probably burning about 6,800 calories a day.

Lab work I had done before and after the hike showed that many of my physical systems crashed. My body had down-regulated to keep up, and that probably limited my recovery and performance.

A good tip for you: If you’re trying to increase your performance and don’t want to change your bodyweight, use your scale weight as your guide. Weigh yourself daily and look at weekly trends.

If your weight trends downward, eat slightly more food. Add 100 to 200 extra calories and continue watching your weight. Repeat and monitor trends.

4. Be curious. Be kind.

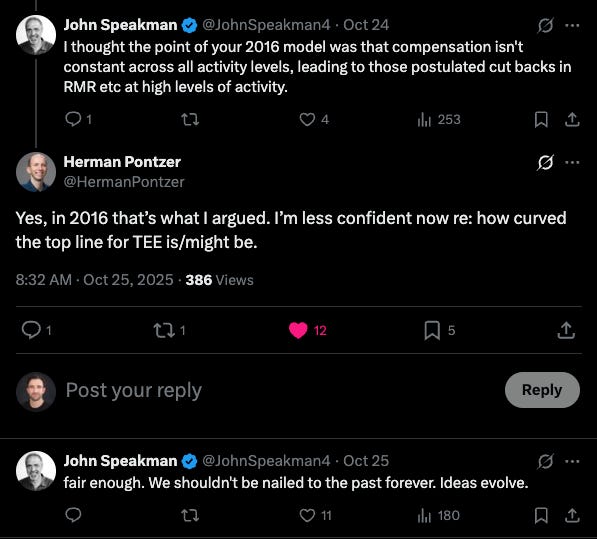

On social media, Pontzer tweeted some criticisms of the PNAS study and Speakman weighed in. They had a back-and-forth about the details of each of their studies.

And it ended with this:

Imagine that. Two people, on the internet, having a kind exchange where they admit they aren’t perfect, have changed their mind on an idea, and still have more to learn.

Have fun, don’t die, ideas evolve,

Michael

Thanks to our partners

Jaspr air purifiers

Air quality is a massively overlooked health metric. I consider Jaspr my #1 home health tool. Most health-promoting things require effort—but Jaspr is an exception. Just plug it in and remember to breathe. Get a discount through this link.

GOREWEAR

I’ll be packing GOREWEAR gear on a long hike today. Specifically, the CONCURVE WINDSTOPPER insulated jacket which cuts the wind and cold. Check it out. EASTER gets you 30% off your first GOREWEAR purchase. It’s pure Gear Not Stuff.

Maui Nui

Maui Nui harvests the healthiest protein on planet earth: wild (and invasive) axis deer on Maui. The nutritional value of axis deer is incredible. My go-to: The 90/10 stick. Head to mauinuivenison.com/lp/EASTER to secure access.

Pontzer H, Durazo-Arvizu R, Dugas LR, Plange-Rhule J, Bovet P, Forrester TE, Lambert EV, Cooper RS, Schoeller DA, Luke A. Constrained Total Energy Expenditure and Metabolic Adaptation to Physical Activity in Adult Humans. Curr Biol. 2016 Feb 8;26(3):410-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.046. Epub 2016 Jan 28. PMID: 26832439; PMCID: PMC4803033.

Raichlen DA, Pontzer H, Harris JA, Mabulla AZ, Marlowe FW, Josh Snodgrass J, Eick G, Colette Berbesque J, Sancilio A, Wood BM. Physical activity patterns and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk in hunter-gatherers. Am J Hum Biol. 2017 Mar;29(2). doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22919. Epub 2016 Oct 9. PMID: 27723159.

Howard KR, Prado-Nóvoa O, Zorrilla-Revilla G, Laskaridou E, Reid GR, Marinik EL, Stamatiou M, Hambly C, Davy BM, Speakman JR, Davy KP. Physical activity is directly associated with total energy expenditure without evidence of constraint or compensation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025 Oct 28;122(43):e2519626122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2519626122. Epub 2025 Oct 21. PMID: 41118225.

This even held among the most active runners, who we’d assume would have the most compensation.

One hypothesis of the constrained model is that when people exercise a lot, they just get lazier elsewhere during the day to save calories. They might run 10 miles, but afterward sit around on the couch and fidget less. The PNAS study found the opposite: the exercisers generally had less sedentary time.

von Loeffelholz C, Birkenfeld AL. Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis in Human Energy Homeostasis. [Updated 2022 Nov 25]. In: Feingold KR, Ahmed SF, Anawalt B, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279077/

Morss GM, Jordan AN, Skinner JS, Dunn AL, Church TS, Earnest CP, Kampert JB, Jurca R, Blair SN. Dose Response to Exercise in Women aged 45-75 yr (DREW): design and rationale. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004 Feb;36(2):336-44. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000113738.06267.E5. PMID: 14767260.

Excellent post. I swear by my walking pad for this reason. Much of my life is now virtual over the computer. Merely by walking while doing calls I accumulate an extra five miles per day on average I otherwise would not have had. One of the best investments I have ever made.

Great post! I always quote whomever it was (can’t remember the source; maybe you?) that noted, “I can burn 600 calories in an hour with exercise. I can consume 600 calories in 5 mins with a single 20 oz frappa-mocha-chilly-whippy* drink. Caution advised.”

*Not a direct quote, obv.