RFK Jr.'s New Dietary Guidelines: Good, Meh, or Dumb?

Why "eat real food" is great advice, but the new inverted pyramid might actually lead you astray.

The Two Percent New Year Challenge is now live. Become a Member to join. If you want 2026 to feel different—better, clearer, more capable—this is your on-ramp. Here are more details about how it works and the science of why it’ll help you change.

On Wednesday, the Department of Health and Human Services, led by Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and the USDA released the new Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

These guidelines come out every five years. They shape how we’re told to eat for health and influence massive federal food programs—from school lunches to SNAP.

The headline message of the new guidelines is simple:

Eat real food.

Who could argue with that?

But once you dig into the actual documents1, a more complicated picture emerges. Beneath some genuinely good updates, there’s ambiguity, internal inconsistency, and a few decisions that are hard to defend—scientifically and logically.

Today, we’re breaking down what’s actually in the new guidelines—and what they mean for you.

You’ll learn:

Why the shift from complex “dietary patterns” to simple “real food” language is likely a win for public health communication.

Why the new push for high protein and full-fat dairy might backfire and cause weight gain for the average American.

How the new inverted pyramid graphic directly contradicts the report’s own math.

The misleading yogurt comparison that suggests someone was massaging the numbers to make a point.

The one critical nutrient the report surprisingly downplays that you definitely shouldn’t ignore.

Let’s roll …

Quick Housekeeping

In case you missed it:

On Wednesday, we looked at the new science of controlling hunger—the key to losing or maintaining your weight. Read the post for 8 ways to control hunger.

On Friday, we ran a Gear Not Stuff—our first ever to feature just one piece of gear—on a cardio machine that I love.

My new rucking manual—Walk With Weight—comes out 2/24. Get a signed copy here for 15% off.

Thanks to our partners:

Janji, an independent running brand making gear built for ultra-distance pursuits. They’re the only brand making gear specifically for 200-plus-mile adventures—my favorite kind. Check out the Circa Daily Long Sleeve, great alone on cool days or as a layering piece on the coldest days. You can find Janji at Janji.com and at REI stores nationwide.

Function Health, which offers 5x deeper insights into your health than typical bloodwork. You’ll learn critical information that can guide you into feeling better every day. It helped me identify a mineral insufficiency. Go to my page here to sign up, receive a discount, and pay just $340.

Maui Nui: Eat ethically. Maui Nui’s harvests wild Axis Deer, which are invasive to Maui. They’re also the healthiest meat on planet earth. Try the Stick Starter 6-Pack at $39 each. High-protein, low-calorie, and wildly clean.

A big change: the new food pyramid

If people remember one thing about federal nutrition advice, it’s usually the food pyramid.

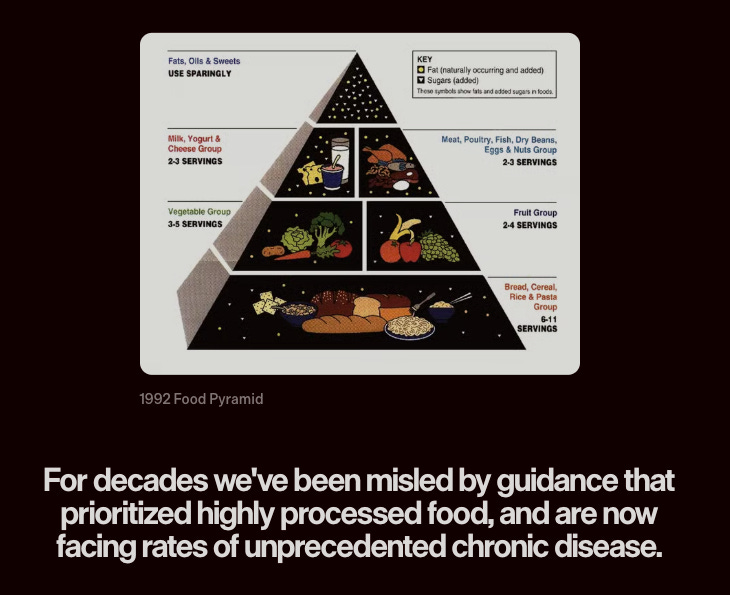

Food pyramids—which are used by many countries—are a simple way to communicate what to eat and roughly how much. Most people will remember the USDA’s original food pyramid, which ran from 1992 to 2005 (pictured below), before being replaced by MyPlate in 20112.

RFK Jr. and others have been highly critical of the old pyramid. The new realfood.gov website presents it as a root cause of America’s health problems. From the website:

That claim doesn’t hold up.

Look closely at the old pyramid: Most of the foods it depicts are minimally processed3.

Side note on food pyramids: Plenty of countries have food pyramids nearly identical to our old one, pictured above. E.g., Japan and Bangladesh. Yet their obesity rates are 3-4%, compared to 40% in the U.S. This strongly suggests the pyramid itself didn’t cause our ill health.

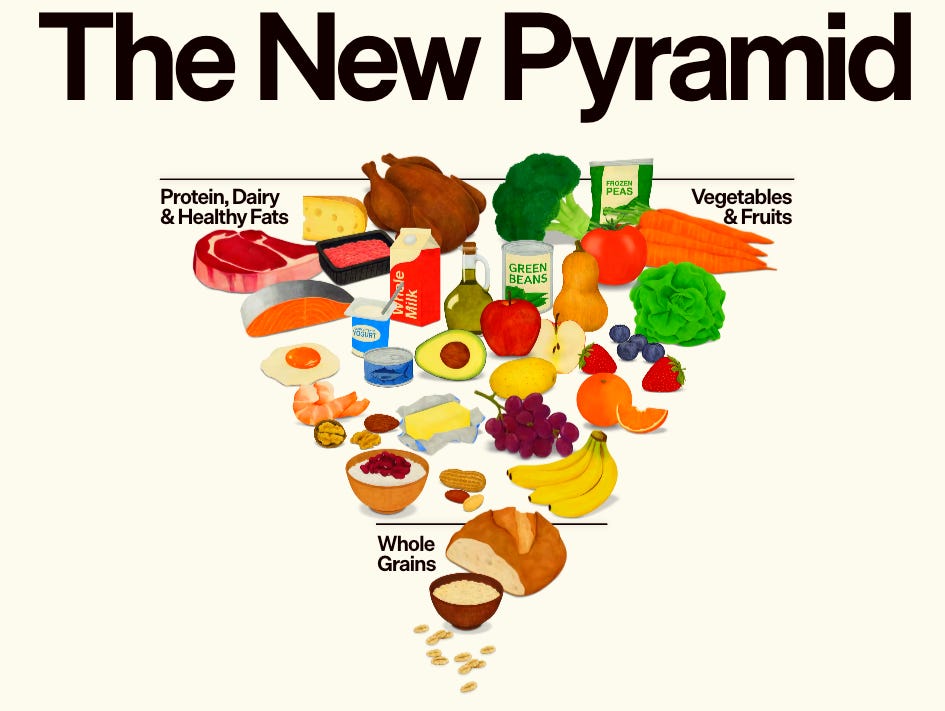

Nevertheless, the administration introduced a new graphic: an inverted food pyramid, meant to signal different priorities.

✅ The good:

“Eat Real Food”

The second paragraph of the new guidelines lays out its ethos:

The message is simple: eat real food.

This is a meaningful shift in language.

Previous guidelines emphasized “healthy dietary patterns.” Translation: Eat nutrient-dense foods across all food groups within calorie limits.

The idea of dietary patterns was scientifically sound and well-meaning. It got us away from talking about foods and nutrients in isolation, and accounted for the fact that foods work together to impact our health.

More info on that: Think of a healthy diet like a symphony. While an individual instrument (a specific food) or a single note (a nutrient) has its own sound, the final impact on the listener (your health) is determined by how all the instruments and notes play together throughout the entire performance (your overall diet).

“Dietary patterns,” the scientists believed, allowed people to tailor their diet to their personal preferences, cultural traditions, and budgetary considerations while still eating healthy.

The framing is accurate—but it’s also abstract. Telling the average person to “eat a healthy dietary pattern” usually requires five minutes of translation before landing on: eat mostly unprocessed food from a variety of sources.

“Eat Real Food” conveys the same idea more quickly and clearly.

The underlying message hasn’t changed—eat less junk food and more whole foods—but the delivery has improved.

The basics are still intact

Because some of RFK Jr.’s ideas around health are widely considered fringe by the scientific community, there was real concern about what these guidelines might include.

The infectious disease researcher Neil Stone joked on Twitter:

Instead, the core advice remains solid and familiar:

Eat lots of vegetables and fruits (these are at the top of the inverted pyramid).

Choose whole grains over refined grains.

Limit added sugars and avoid excess sodium.

Reduce intake of highly processed foods (i.e., junk foods high in added sugars, sodium, and saturated fat).

As the Stanford nutrition scientists Chris Gardner wrote, “These messages are consistent with decades of research and remain foundational to improving health.”

⚖️ Somewhere in the middle:

Eat more protein

The new guidelines increased the recommended daily protein intake from 0.8 grams per kilogram of your bodyweight to 1.2-1.6 grams.

That could help some populations—particularly older adults at risk of muscle loss (though physical activity still matters far more than protein intake).

But there’s a tradeoff.

As Harvard nutrition scientist Dr. Deirdre Tobias pointed out in a press conference, protein is the one nutrient Americans already get plenty of. The average American already meets the low end of this new, higher protein recommendation4.

If we eat even more protein (especially from animal sources, as the report pushes) two things can happen:

People add even more protein without removing other foods, increasing total calories and weight, which could do more harm than good.

Protein displaces other healthy foods, often fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains, which Americans don’t get enough of. “Fruits, vegetables, etc—those haven’t changed in these new guidelines,” said Tobias,” so there’s no reassurance that we’ll have improvements for those key groups.”

This is where the older “dietary patterns” framing actually helped: it encouraged balance and variety rather than prioritizing one macronutrient over others.

Full-fat dairy

Previous guidelines discouraged full-fat dairy. The new guidelines recommend it.

That’s defensible. Full-fat dairy appears largely neutral for heart health, and fermented versions (like yogurt and kefir) may offer mild gut health benefits.

But there’s a practical issue: if someone swaps low-fat dairy for full-fat across the board, calorie intake rises—without strong evidence of additional benefit for most people. Low-fat dairy still provides protein, calcium, and probiotic effects.

Over time, those extra calories can matter. Weight gain remains one of the strongest drivers of disease.

❌ The Bad

The saturated fat math doesn’t add up

The guidelines retain the long-standing recommendation to limit saturated fat intake to no more than 10% of calories.

“That was incredibly reassuring for me,” Dr. Tobias said, “because I did hear through previous press announcements that the administration might remove it.”

At the population level, higher saturated fat intake reliably raises LDL cholesterol and ApoB, increasing cardiovascular risk for a meaningful subset of people—especially those genetically predisposed. Dr. Peter Attia recently explained the roles of LDL and ApoB in heart disease.

But then there’s the new pyramid.

Look at it. If someone followed the inverted pyramid visually, they’d dramatically increase how much red meat, butter, and full-fat dairy they eat—major sources of saturated fat.

FFS, butter sits in the middle of the pyramid, above whole grains! Controlled trials consistently show butter raises LDL cholesterol more than unsaturated fats like olive or canola oil. Some people tolerate this. Others don’t.

As the nutrition researcher Kevin C. Klatt, PhD, RD wrote, “The recommendation is clearly endorsing high animal fat intakes, which will result in high saturated fat intakes.” The math doesn’t math.

Not much mention of fiber

Fiber is one of the most consistently beneficial components of a healthy diet—and one Americans chronically under-consume.

One recent review5 notes, “Research has shown that increasing fiber intake can reduce the risk of various chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD), type II diabetes, obesity, colon cancer, and inflammation … By synthesizing data from multiple sources, we found a clear association between higher fiber intake and a lower incidence of these diseases.”

But fiber is downplayed in the report. That’s not ideal6.

The graphic clashes with the text

If you look at the new inverted food pyramid, you’ll walk away thinking it’s telling you to avoid whole grains.

After all, whole grains are at the bottom—the pyramid features just three foods representing them: bread, rice, oats. Meanwhile, there are 11 animal-based foods at or near the top.

But the written guidelines recommend 2-4 servings of whole grains a day. If the graphic matched the written advice, the whole-grain section would be substantially larger.

That’s confusing.

The administration says the graphic is a “priority map,” but that doesn’t solve the confusion. It creates it.

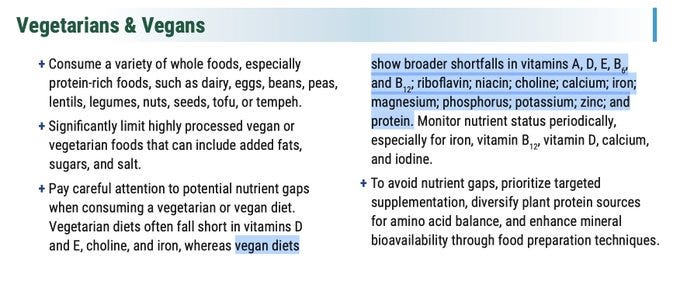

Selective criticism of diets

Vegetarian and Vegan diets were called out for having nutrient gaps.

It’s true that a poorly formulated vegan diet (basically just going vegan without considering what nutrients you might be sacrificing) can lead you to have nutrition gaps.

But similarly restrictive diets popular within the MAHA movement—most notably carnivore diets, which carry more apparent and stronger nutrient gaps—go unmentioned.

My take: If you’re going to call out restrictive diets for nutrient gaps, call them all out, not just the ones your political in-group dislikes.

Conflicts of interest

One of RFK Jr.’s main critiques of the old guidelines was that they were written by people with conflicts of interest/ties to the food industry.

He promised to “toss out the people who were writing the guidelines with conflicts of interest” and form a panel that “have no conflicts of interest.”

But that’s not what happened:

The ties were, unfortunately, to industries that got the most love in the guidelines. Whether those ties influenced decisions is a separate question—but the promise of a conflict-free panel wasn’t kept.

Bad and inaccurate comparisons

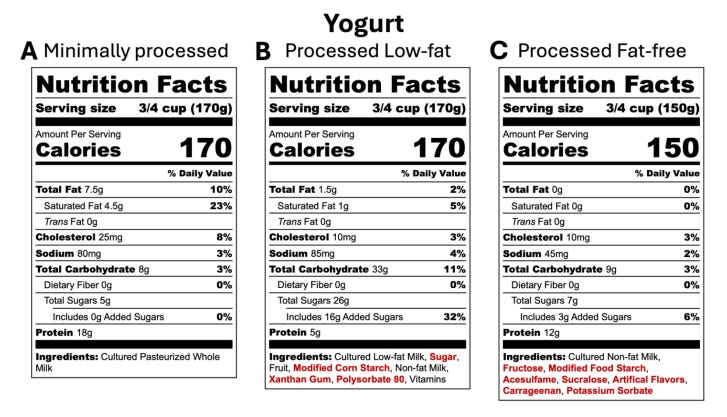

To make their case for full-fat dairy, the report compares three yogurt labels:

“Minimally processed” (full fat)

“Processed Low-Fat”

“Processed Fat-Free”

Here’s their graphic:

The problem: The comparisons are fatally flawed.

The minimally processed full-fat yogurt is plain Greek Yogurt. It has 18 grams of protein and zero sugar.

Example B is non-Greek and sugar-sweetened (not plain) yogurt. That’s why it has 16 grams of added sugar and only 5 grams of protein. They should have used a low-fat plain Greek yogurt for a fair comparison. That yogurt would have 50 fewer calories (120 total), zero sugar, and 15 grams of protein.

Example C is a fat-free, flavored yogurt whose calorie count is all wrong. Based on the listed protein and carbs, it should have 80-90. Someone clearly made up the figures to create the graphic, because the math doesn’t work.

This is just one example of questionable comparisons and number-bending we’re dealing with in this report.

This example also highlights my previous point: If you swap low-fat or non-fat dairy for full-fat, your calories go up. And that could lead you to gain weight, and being overweight or obese seems to be the primary driver of health issues (more so than individual foods).

My big takeaway

These guidelines aren’t a complete disaster.

They aim to push Americans toward real food—a goal shared by every previous version, just communicated more clearly here.

But they also push more meat and saturated fat into a population that already consumes plenty, while visually de-emphasizing whole grains and underplaying fiber—one of the most protective elements of diet we know.

The documents feel rushed and inconsistent. Like they needed one more pass from an editor and a fact checker willing to say: this doesn’t add up.

So yes: eat real food. Just don’t outsource your judgment to that new pyramid.

Have fun, don’t die, eat real food (but maybe ignore the graphic),

Michael

Audio version

Those that are processed, like pasta, are often fortified to include vitamins like folate. That’s one reason why the old guidelines were OK with some levels of grain processing—folate is critical for pregnant women. The new guidelines may lead pregnant women to not get enough folate, which can lead to neural tube defects in babies. More here.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. (2024). Table 1. Nutrient intakes from food and beverages: Mean amounts consumed per individual, by male/female and age, in the United States, August 2021–August 2023 [PDF]. What We Eat in America, NHANES August 2021–August 2023. Link.

Alahmari LA. Dietary fiber influence on overall health, with an emphasis on CVD, diabetes, obesity, colon cancer, and inflammation. Front Nutr. 2024 Dec 13;11:1510564. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1510564. PMID: 39734671; PMCID: PMC11671356.

Thinking out loud, the assumption could be that by emphasizing fruits and vegetables, fiber intake will take care of itself. But the same logic could be applied to protein: telling people to eat more meat and dairy would also “solve” protein intake. So, TLDR, I’m not sure what happened with this one.

Also interesting that alcohol limits were removed.

My first thought when seeing the new pyramid: Michael Easter isn’t going to like seeing oatmeal in the bottom 1/3.

My second thought: where’s the McDonalds, Monsters, and Nerd Clusters?

My third thought: yeah I should probably ensure I get my 5 servings of fruits and vegetables every day.